Originally published in Adventure World Magazine, Spring 2003

“Sarah Boardman?” Mike said, incredulously. “You mean the Sarah Boardman?” I sighed. I hadn’t expected it to be a hard sell. “She’s really very nice,” I protested, weakly. “I spent all week with her at the Academy. She actually came here as a student.” Mike shook his head, unconvinced. “You’ve never actually seen the Eco-Challenge New Zealand, have you?” he asked. I had to admit, I hadn’t. I’d heard about it, of course, but I didn’t have cable TV at home. I was still searching for a further defense when Mike wandered off to find our teammate Mark and tell him the news.

Earlier in the week, I’d been working as a volunteer for Odyssey’s seven-day adventure racing academy. It seems I was the only person, out of 25 students and instructors, who didn’t know who Sarah Boardman was. We did introductions on Monday afternoon, and when it was Sarah’s turn she stood up and told us, a little defiantly, “I never asked to be a TV drama queen, and I don’t want to be in charge of anyone. I’m just here to learn and become a better racer, and hopefully to find some new friends and teammates.” I leaned over and whispered to Joy Marr, co-director of the Academy, “What’s she talking about?” Joy looked surprised. “Haven’t you seen the last two Eco-Challenges?” she asked me. I shook my head. “Well, they pretty much demonized Sarah,” Joy explained. “She had some…team dynamics issues, you know.”

As the Academy classes progressed throughout the week, I kept my eye on Sarah, looking for evidence of the demon I kept hearing about. I couldn’t find any. Sarah was helpful, eager to share her experience, and had a humorous and easy-going manner with the other students. As the Academy students began to form their teams for the Endorphin Fix at the end of the week, however, two of them got left out: Sarah, and a rookie named Michael. Michael, an accountant with the IRS, had never even been on a mountain bike before this week. The Effix is commonly known as the toughest two-day race in the country, and it was clear that if Michael was to make it through even part of the race, someone had to take him under their wing. Sarah was the obvious choice.

But Sarah wasn’t so sure. “I’m worried about being responsible for his safety,” she told me on Thursday. “I came here to learn from other racers, not to be in charge of someone else.” I’d heard enough about New Zealand to understand her point, by now. I had just found out that morning that one of my own teammates was going to be a no-show tomorrow. He was a police captain in Cincinnati, and a work crisis had caused his last-minute withdrawal from the race. I wanted to recruit Sarah, but I couldn’t influence her decision about whether to race with Michael–then Michael would have nobody. I struggled to keep quiet as Sarah worked through her options.

“I could race solo,” she mused. “But I’ve done that several times before, and it hasn’t gone well. Or, I could just go home after the Academy is over and skip the race.”

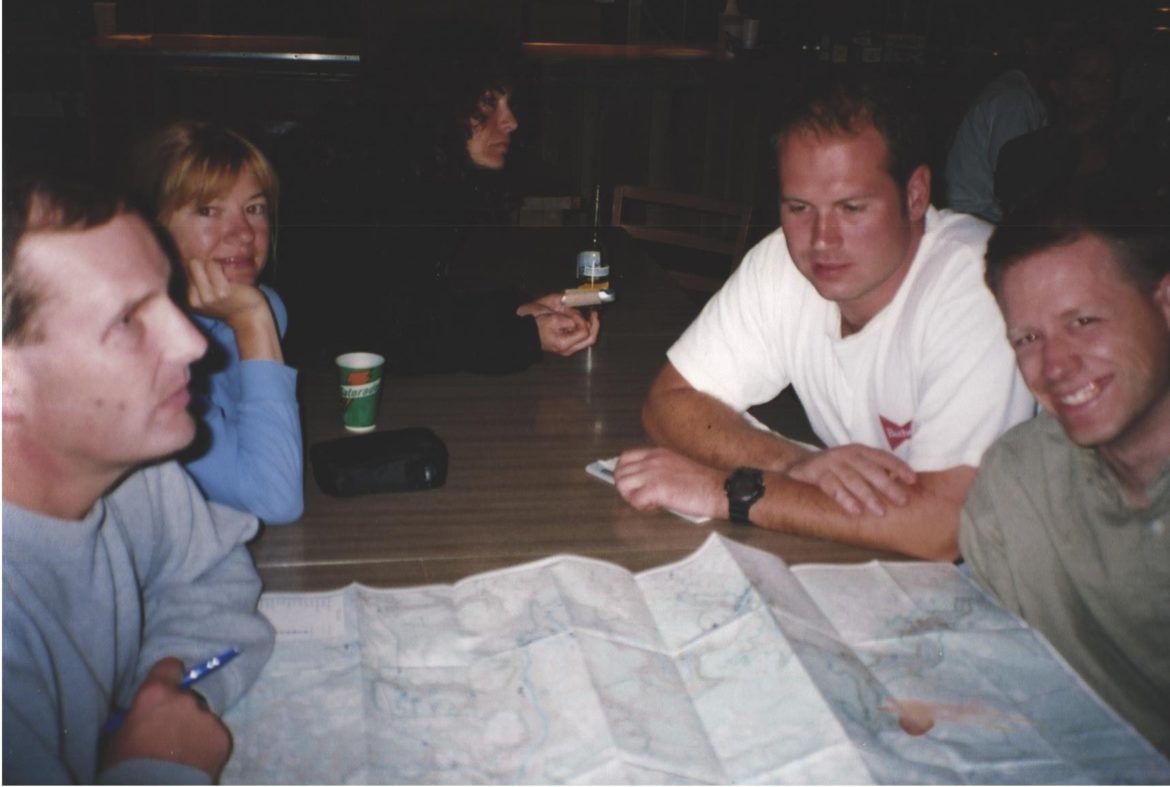

By Thursday afternoon, Sarah was tormented by indecision and was leaning towards not racing at all. I sat down with Don Mann, the Academy director, and some of the other instructors to try and brainstorm a solution. To have any of the students miss out on the Effix experience would be a major disappointment. We sketched out various scenarios on scrap paper until we finally came up with a solution: we would register Sarah as my fourth teammate, and Michael would register as a solo, to be brought along with us. We would be Beer Nuts and Beer Nuts Too, a team of five. If Michael dropped out, we would remain official, since he was registered as a solo. It was perfect, but for one thing: my teammates knew nothing about it until they arrived on Friday afternoon.

To their credit, Mike and Mark sucked it up fast. Within an hour, they were joking about the dubious distinction of having two accountants named Michael on the team. We called them Mike and Michael to avoid confusion.

As always, the race started at midnight on Friday to the sound of Jimmy Hendrick’s Star Spangled Banner. I was surprised to find that Michael could keep up a pretty good pace on foot. I had assumed that he would hang in there for 12 or 16 hours, then DNF and leave us to finish the race without him, but he seemed doggedly determined from the beginning. Sarah and I battled sleep monsters toward early morning, staggering back and forth on the trail and occasionally bumping into each other, but Michael scrambled happily up ahead, chatting with Mike and Mark. I began to think that perhaps we had a chance of finishing with him. And Sarah’s experience level, far higher than our own, was quickly proving to be an advantage. She handled logistics with skill and ease, co-navigating with Mark, reminding Michael to eat and drink, and making decisions about who should carry what gear in order to equalize the team’s strengths and weaknesses. Most importantly, she took complete responsibility for Michael. From the beginning, he followed her every move as if she were his mother.

We were in for a rude shock at the bike transition, however. After a freezing swim across the New River, we arrived at 9:00 am, aware that we had little if any chance of making the canoe cut-off at noon. We picked up our bikes and headed for a brutal climb up Beury Mountain, and Michael’s inexperience became painfully apparent. We pulled over on the side of the road a mere five minutes into the climb.

“Let’s get some stuff out of his pack, first of all,” Mike said.

His brow furrowed, Mark asked us, “Did you notice that he only rides in one gear?”

“And did you know he has asthma?” Sarah asked me. This was news to me. I guess I hadn’t been paying much attention during the Academy bike rides. When Michael finally pulled up, breathing heavily, Mike peered into his pack and began to divide up the contents between us, a process we would repeat several more times until Michael had nothing left in his pack. I had bought a bike towing system on the internet several weeks ago, but unfortunately, we couldn’t figure out how to use it and had left it back at the race start.

It took three hours to reach the top of the climb. At first, Mike and Mark and I would peddle ahead, then lie in the grass on the side of the road and catch a few minutes of sleep while we waited. I felt increasingly miserable. The three of us had been racing together for two years and had always had great team dynamics—that perfect situation where everyone understands each other’s hot buttons and no one ever gets on anyone’s nerves. But I had never tested the team’s patience like this before. On our third or fourth stop, I couldn’t stand the guilt anymore. “Why don’t you guys go ahead, you still have a chance for an unofficial finish,” I told them. “Sarah and I can stay with Michael; we’re the ones who made a commitment to him.”

“Don’t be silly,” Mark said simply, and that was the end of it.

Sarah pulled up, Michael trailing just behind her, and whispered to us, “let’s take turns!” We began to alternate so that one of us was always riding with Michael, coaching him to use his gears and to keep peddling on the flats. Michael was clearly exhausted and would sometimes stop and put his head down on the handlebars. But he was determined. At one point he looked at me and shouted, defiantly, “I know I’m wrecking your race! I’m not giving up though.” You had to admire his resolve; he was clearly not going to quit. So we focused on improving his bike skills, and eventually he did begin to improve. Later, we joked that he had progressed from a beginning biker to an intermediate in the short space of a single race.

We reached the top of Buery Mountain and the section that followed was twisty singletrack through the woods, dotted with mud puddles, and a deep garbage-filled ravine which we handed our bikes through. Sarah was stung by a bee and informed us that she was allergic. She took an Allegra, which made her woozy, and we had a new biking challenge: keep Michael moving, and keep Sarah from crashing.

At checkpoint 6, a race volunteer waved frantically at us as we climbed out of a ravine. “Give me your radio!” she shouted. “We have a medical emergency, I need to call an ambulance!” Mike handed her the radio and she called for help. A woman riding an ATV, unrelated to the race, had plunged into the ravine right next to the CP. She was in bad shape, with apparent back and head injuries. In West Virginia, ambulances are private enterprises, and any number of them might respond to a call. The checkpoint became a hectic mess of squealing brakes, flashing lights and screaming sirens as a ridiculous number of ambulances screeched into the dirt parking lot. While we waited to get our radio back, Sarah was stung by another bee.

“What does that mean?” I asked her, concerned. “Can you handle two bee stings?”

“I don’t know, I’ve never had two before,” Sarah replied, looking a little worried. We slumped over our packs on the side of the road, figuring we’d better stay near the ambulances in case Sarah needed one. It occurred to me that this was becoming the most interesting race I’d ever had.

Half an hour later, Sarah decided she was OK, and climbed dizzily back on her bike. We made the canoe transition at 5:00 pm on Saturday—a mere five hours beyond the cut-off point. To miss this transition was deeply discouraging, as it meant that we would forgo both the canoe and the whitewater swim on the New River, and would bike both sections instead. We had already been on our bikes for eight hours, and now we faced another ten hours or more. We began to talk defeatedly about how we might as well continue until the race officials pulled us off the course.

As dusk approached, we followed a dirt road along the river, climbing several steep hills. A rattletrap old Chevy met us coming down the road, and two scruffy-looking local West Virginians pulled over to chat with us. “Watch out fer bears up here,” one of them said, with genuine concern for our safety.

“Yep, they’re out here. D’ya have a pistol with ya?” the other one asked, apparently serious. With bemused glances at each other, we assured them that although we were unarmed, we would be careful.

Michael was riding much more competently now, and we moved at a faster pace. Just before we reached CP9, I heard the sickening sound of a bike crashing and sliding on the road ahead of me. I rounded a corner to find Sarah lying on the pavement, curled up in a fetal position with Mike standing over her. She was momentarily paralyzed, inventorying her body for broken bones. Amazingly, she found herself to be OK, without even much road rash. But the Allegra was clearly making her unstable on a bike, and this was only the beginning of the bike crashes for her.

After the river transition, the mountain biking terrain became more interesting, changing from dirt roads to single-track along the river. After dark, we arranged ourselves according to lighting systems—NightRiders in front and back, cheap lights in the middle—and I called out obstacles as I encountered them. “Mud puddle, go left! Roots, hang right!” We sharpened up the effort after Sarah had another crash. At one point the track skirted a dizzying drop-off, and Mike hit a root and catapulted toward the cliff. In a spectacular self-rescue, he caught a tree with one arm just before going over the edge. We stopped for a moment of silence to marvel at how close we came to needing an ambulance again.

“I’d probably leave out this part of the story when you get home to Annette,” Mark suggested. Annette, Mike’s brand-new wife, had just recently agreed to let Mike come back to the team after a year’s absence.

At 1:00 am on Sunday morning, we came to a punch point situated near some cement block toilet stalls along the river. Sleep deprivation had become a problem for everyone except Mike, but it was too cold to sleep. The toilet stalls were warm, and the floors, while hard cement, were spacious enough to fit several people. Mark, Sarah and I settled in for a map check, and I fell asleep. When I woke up, an argument had begun over whether we had time for a fifteen-minute nap.

“Well,” I interrupted in my best smartass tone, “while you guys have been arguing about whether we can take a fifteen-minute nap, I’ve been taking a fifteen-minute nap.” Sheepishly, Mike agreed to let us doze for a few minutes. But as soon as we fell asleep, there was a knock at our door. “Chris?” someone called through the door.

I woke up, confused. “Yes?” I responded.

“Are you coming out?” the racer asked.

“Yes, in a minute,” I said.

Sarah nudged me. “Anna,” she whispered. “You’re not Chris.”

I paused, considering. “Oh yeah, right,” I finally responded, in a state of complete befuddlement. It’s moments like these when you wonder what the hell possesses you to be a racer in the first place. I tried to explain myself to the anonymous racer, still talking through the door. “I’m not really Chris,” I said apologetically. “I know who Chris is, she was at the Academy, but I haven’t seen her since the last checkpoint.”

Chris’s teammate didn’t believe me. He came back every two minutes, banging on our door and demanding that Chris come out. Finally I opened the door and showed him my face.

“She’s not in here, honestly,” I told him. “I was just confused.” He went away, as befuddled as I had been.

Mike told us it was time to get up. We walked our bikes up a steep and seemingly endless road and took a forest trail in search of Kaymoor Top. Until this point, the navigation had gone well, but now we were in unfamiliar territory. We were traveling with ten or twelve other teams who had made the same navigational error we had, and so it seemed inconceivable to us when we came out on what we assumed to be Kaymoor Top and couldn’t find the checkpoint. We wandered around a small West Virginia village for several hours, trying to figure out where we’d gone wrong. A mangy stray dog followed us everywhere, and we named him Dingo. Finally, at about 4:00 am, we realized had little chance of figuring out our mistake before dawn. We decided to sleep until the sun came up and hope that rest and sunlight would turn things around for us.

Other teams had made the same decision, and the trail was littered with bodies wrapped in space blankets. Sarah, the logistics queen, organized a bed for us with a layer of dry bags, then PFDs for cushioning, then space blankets on the bottom to keep us dry. We would spoon together for warmth and share two space blankets as cover. This plan would have kept us marvelously warm if Michael had not decided to wrap himself in one entire blanket and uncover me. My fruitless attempts to wrestle the blanket back from him kept Mike awake for most of the three hours until dawn.

We woke at 7:00, feeling refreshed, and surprised to see that Dingo was still hanging around. He was skittish and would not come close to be petted, but we couldn’t shake him either. The sun gave us new energy and enthusiasm, and as we successfully navigated our way to the real Kaymoor Top, we sang in unison, “D-I-N-G-O! D-I-N-G-O! D-I-N-G-O, and Dingo was his name-O!”

At the checkpoint, we were greeted by Hugo and Top, volunteers from the Academy. There was a small camp store, with shelves nearly emptied by racers, but we found Klondike Bars and hot oatmeal, and a passing camper donated leftover crackers and Cheese Whiz to our feast. We sat on the front porch of the camp store, stuffing our faces, not talking. Chris, the woman whose teammate had been looking so persistently for her in the toilet stalls, showed up at the CP alone. Her entire team had quit during the night. We figured she’d be a good fit for the Beer Nuts team—after all, last time we’d seen her she’d been boogying to “Paradise by the Dashboard Lights” at CP 9—so we invited her to join us and became a team of six.

After 21 hours on our bikes, we loaded them on a truck and returned gratefully to trekking, complaining about diaper rash. I consulted Hugo and Top on our course while everyone re-organized gear.

“I know we haven’t a prayer of finishing the entire sport class course before Monday morning, at this point,” I told Hugo. It was now 9:00 am on Sunday, and the course cut-off was 4:00 pm. “What do you recommend, if we just want to catch as much of it as we can?” Hugo spread out a map in front of Mark and traced our route with one finger.

“Well, you already missed the rappel cut-off,” he said. “I would continue as far as you can on foot, skip the Endless Wall section, and when you get too tired or it gets too late, take short-cuts on the prohibited roads to get to the final bike transition. You’ll be unofficial, but you’ll still cross the finish line.” It seemed like a good plan. Sarah put Michael on a tow rope, and we set off down the trail toward CP 11. The weather was fine and sunny, and we were happy to have a new teammate. But our cheer didn’t last long. Several hours later, in the town of Fayettesville, we became disoriented again and stopped for a map check.

I think it was me who came up with the preposterous suggestion first. Everybody laughed. “Take a cab, yeah right!” Chris said. Mark and Mike exchanged glances; they knew I was serious. “We’re not going to finish the course anyway,” I said. “And we might get in trouble for taking prohibited roads. So why not take a cab to Winona, grab a beer at the Winona Pool Hall, and then pick up our bikes and ride to the finish?”

It didn’t take long to convince everyone. It was mid-day on Sunday, mere hours from the race cut-off, and we were still so far from the finish that people would have missed their Monday morning flights if we continued on foot. We sat on the grass of the Fayettesville Park while Sarah bravely knocked on doors in search of a phone. She must have been a sight for the neighbors, filthy as we all were, but the first folks to answer the door let her in to use the phone. Within twenty minutes, the six of us were in a taxi-van headed for the tiny backwater town of Winona.

They were happy to see us at the pool hall, Winona’s only public establishment. The owner, a friendly local woman with a thick West Virginia accent, had stayed open through the night to serve burgers to hungry racers. One of her customers got up and helped serve us. We sat on bar stools eating hamburgers and drinking beer for an hour or so. One of the checkpoint volunteers, still laughing about how we had arrived in a cab, commented, “You guys are having so much fun, we should send a cameraman to follow you around.”

“Yeah!” we shouted, giggling. “No!” Sarah countered, frowning. We laughed harder, thinking about Sarah’s perspective on the idea. It was getting more and more difficult to see how the cameras could have turned this woman into such a monster in New Zealand.

Finally, we climbed wearily back on our bikes for the 20-mile ride back to the finish line at Camp Washington Carver. A van full of race volunteers, knowing we were already unofficial, stopped to take our packs. Sarah, Mike and Chris formed a towing/pushing line to get Michael up the hills to the Camp, often scrambling in front of him and nearly crashing several times. Mark and I rode up ahead, assessing the race.

“You guys have been awesome,” I told him. “I wouldn’t have blamed you for being mad at me for recruiting teammates we didn’t even know.”

Mark shrugged. “You know me better than that,” he said, with his usual easy-going manner. “I’m disappointed that we didn’t finish again, but I have to admit, this has certainly been one of our more interesting races. And there’s always next time. Someday, we’ll actually finish this damn thing.”

Finally, at 5:00 pm, an hour past the official cut-off, we arrived at the finish. We rode in formation, and when we reached the finishing gate, Michael stumbled off his bike, went down on one knee, and sobbed out loud. His emotional pride at having “finished” the race was so touching that some of the race organizers were teary-eyed themselves when they congratulated him.

Sarah was pretty excited to see the fruits of her mothering labor pay off. As Michael sobbed, she bunny-hopped her bike along the road—and crashed, once again, on the pavement in front of the finish line.

I couldn’t stop laughing. “I don’t care about all that Eco-Challenge stuff,” I told her. “We’ll race with you again anytime.”

Comments are closed.