A uniformed policeman with slick, coiffed hair combed straight up in the Iraqi style came into the waiting room and said, “Anna! Please come.” He held a sheaf of papers in front of him and I could see they included our visa applications. I jumped out of my chair and hurried to the front of the room. “Karen! Ina!” he continued. We gathered in front of him.

“We need original,” he said.

I didn’t understand at first. Original? Original what?

Karen got it first. “Hotel reservation?” she asked. He nodded. Karen messaged Haidar, our guide, who was waiting for us outside the Basra airport. I wondered what would have happened if we didn’t have Haidar. How could we possibly get an original copy of our hotel reservation if we couldn’t get out of the airport?

We sat back down to wait the half hour Haidar said it would take for him to come rescue us and Ina ordered coffee from a man the policeman had brought to us. She handed him $3 US dollars because we hadn’t been able to change any money yet. He came back a minute later and said he needed another $4; surely a scam, but what could we do?

The coffee was from a machine. We waited, and the policeman came to talk to us periodically. He was friendly and spoke passable English. “This guide,” he said, “how did you find him? You are sure he is OK?” It had been more than half an hour and I was beginning to wonder myself. Karen had handled all the communication with Haidar; I’d been too busy with work to help much with trip planning. But Karen and Ina nodded confidently. “We’re sure,” they said.

“What is the name of his company,” the policeman asked, persisting. “Where is he based?”

Karen wasn’t sure. “I don’t know the company name but I think he’s in Baghdad,” she said.

We waited. A Ukrainian doctor was also waiting; something about his company-sponsored visa having been screwed up. He told us he’d been working in Iraq for six years, always as a company doctor for various contractor operations. He gave us safety advice.

“I always have armed security,” he said. “You will need to be careful on your own. Always be polite to men who talk to you. Never argue with them.”

The friendly policeman had advice too. “Don’t carry a purse or a bag,” he said, pointing the travel wallet I had slung over my shoulder. “Use your pockets.” He made a cutting motion, like a street thief cutting the strings of the bag.

My phone chimed; it was a text from Asiacell, the local mobile company Verizon had apparently transferred me to on my international calling plan. “Welcome to the cradle of civilization!” it said. I showed it to Karen and Ina and we took a picture of it. It was true, but I hadn’t thought very hard about it up until now. We were in the place where, in the late 4th millennium BC, the world’s first writing system and recorded history itself were born. The Sumerians, whose descendants we would visit in the Mesopotamian Marshes, were the first to harness the wheel and create city states, and whose writings record the first evidence of mathematics, astronomy, astrology, written law, medicine and organized religion.

Haidar finally arrived. He was young, as we thought; we had joked that we hoped he wouldn’t be disappointed when he found that his clients for the next ten days were three women in their 50s. The policeman grilled Haidar mercilessly, sending him back out of the waiting area to get proof of his legitimate travel agency. He apologized to us when Haidar came back with his documents, but we protested that we were glad he was looking out for us. Always be polite to the men.

We had been up all night to take the 3:00 am flight from Istanbul so we were tired, but we agreed we should make a day of it rather than wasting time going to our hotel. Haidar introduced us to our driver, Ali, and we piled into a comfortable Suburban and headed into Basra. The landscape was desolate at first; long, dusty expanses of dry desert and the flames of methane gas in the distance. When we came into the city it was surprisingly modern in places, with storefronts of floor to ceiling plate glass and glitzy lighted signage. We told Haidar we were hungry and he took us to a restaurant for breakfast. It was filled with smartly dressed college students and Karen asked Haidar to invite one of the young women to come over to our table.

“Where did you get that beautiful abaya?” she asked, and Haidar translated. It was a creamy pale color and open in the front, unlike the uncomfortably heavy black abayas we had bought in Yemen. The woman smiled shyly and told Haidar where to take us shopping.

We made a plan for the day. “We will go to see one of Saddam’s palaces that is now a museum,” Haidar told us, “then we will see the old city. Then we can go to the hotel if you want to rest, and we can go shopping.”

Haidar was casual, funny, easy to be with. We asked him how old he was and he told us 26. We were all old enough to be his mothers; Karen had kids his age. We joked that he would have to put up with three mothers for the next ten days.

Saddam’s palace was on the river and you could see it had once been grand, but now it was surrounded with crumbling stone tiles and garbage. The rooms on the first floor were full of museum cases with old artifacts. Haider told us Saddam had 30 palaces throughout Iraq and hardly used any of them; this one had been gifted to the king of Jordan for his personal use, but the king also never used it.

We went to the old city to see old Ottoman Empire structures lining a canal, wood framed with stained glass windows. Two friendly policeman let us come into the courtyard of one of them. He and Haidar spoke rapid Arabic and Haidar said, “He wants to know how old you think he is?”

We went to the old city to see old Ottoman Empire structures lining a canal, wood framed with stained glass windows. Two friendly policeman let us come into the courtyard of one of them. He and Haidar spoke rapid Arabic and Haidar said, “He wants to know how old you think he is?”

We laughed, afraid to offend him, and Haidar said, “He is 54.” Younger than us. His lined face told a story of war weariness, a hard life in a conflict zone.

We went back to the modern part of the city and saw a dilapidated docked ship that had once been Saddam’s private yacht. Men called to us from a dock, trying to sell a boat ride to the tourists, and we agreed to buy one. The boat took us down the river and back, past riverboat casinos and an amusement park. Sometimes it was hard to believe we were in Iraq. We might have been in New Jersey.

At the mall that evening we tried to find abayas but there were mostly just contemporary clothing stores. Paradoxically, women in black abayas and hijabs roamed aisles filled with jeans and sweatshirts. Haidar told us not to worry, we would find abayas in Nasiyra in two days, the first place where we would need them.

After a comfortable stay and a good night sleep in the Basra Hotel, we set off the next morning for the Mesopotamian Marshes. We stopped at the confluence of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers and saw Adam’s Tree, which Haider explained was believed to be the tree of knowledge where Eve gave Adam the apple. We stopped at a monument site, a memorial to those who fought against Saddam’s regime, and it was closed but when Haidar told the guards we were American and Canadian they opened the gates for us. Grave sites surrounded a large silver domed building and in the middle of the courtyard was a sculpture of a human heart rising from two cupped hands. It was meant to represent the ultimate sacrifice of those who fought.

“Do you think tourism is good for Iraq?” Karen asked. “What do they think of us being here?”

“it’s good,” Haidar said without hesitation. “This is the country of hospitality. You see, they open the gates for you just because I told them you are here from American and Canada.” I thought about that. Yes, we got rid of Saddam. But we also occupied their country, killed many civilians, abused prisoners at Abu Ghraib…what does it take for a people to be so hospitable given the circumstances?

We drove through a crowded market in al Querne and I had my window open. A crowd of policeman standing on in the road, 10 or 15 of them, saw me and stopped the car, asking Ali and Haidar questions in rapid Arabic. I wondered if I should have kept my window shut. Haidar sighed and asked for our passports. He got out of the car and talked to the policeman for a few minutes. When he came back he said, “they just want to know where you are from, what you are doing, why we don’t have security.” He shrugged.

We came to the marshes shortly after and pulled into the driveway of a large domed hut made of reeds. It was shaped like a grand hallway inside, with matts and cushions lining the curved walls and a square gas stove in the middle with tea pots around the edges. The men of the family came to meet us; Raad, his father Abu Raad, and a cousin. Later we met children who were Raad’s younger brothers. We had tea and learned about the Sumerian roots of the Mesopotamian Marshes. Raad said he had a museum and would show it to us after lunch.

We ate on cross legged on the floor, a piece of plastic in the middle serving as a table. The young boys served us grilled carp and big pieces of fresh bread like naan and plates of cucumbers, tomatoes, olives and yogurt. We shared everything, using the bread as utensils. Karen teased Raad that he let his brothers do all the work, especially Raze, who clearly wanted to sit with us. He looked to be about nine years old, and when we went to the museum he came with us and opened the padlocked doors. Raad showed us around proudly. There were artifacts ranging from pottery pieces to old jewelry and a video showing the life of the Marsh Arabs in the 1980s.

It was time for a boat ride in the marshes and I had been looking forward to this. The boats were long and wooden, similar to canoes but coming to a point in the front and back. They had small outboard motors. We took two of them and raced each other down narrow passageways through the reeds. Every now and then we’d pass a water buffalo or two, swimming or standing on the banks. Abu Raad drove ours and sometimes would rock the boat from side to side to spray us or the other boat. We laughed and screamed.

After making a circle through the reeds we went back the other way and came out into the wide open Euphrates. We stopped to talk to a local fisherman and saw the fish on the bottom of his boat. This was how the Marsh Arabs lived, on fishing and selling the milk from their water buffalos. It was a simple life and it looked like it was probably a hard life too, but being on the water was glorious. Haidar promised we would do it again in the morning, in time for sunrise.

We spent the evening lounging on our sleeping cushions under soft, heavy blankets the family brought out for us. We traded our phones back and forth, sharing photos and linking to each other’s Facebook pages. We hadn’t realized this would be like a homestay.

Haidar’s alarm went off at 5:45 but he was the only one who didn’t get up. Abu Raad came in and told him we would miss sunrise and finally he got up. We piled into one of the boats, sitting on the floor under our blankets, and this time we went deep into the reeds, to one of the camps where water buffalo herders lived in crude shacks, surrounded by dung covered reeds and tending their herds. A crumbling paved road cut through the marsh, decayed to nothing in places and no longer passable. We pulled up to a section that was still intact and got out of the boat to photograph the water buffalos up close. They stared at us, unperturbed, chewing their cuds. Calves ran and played amongst them.

“Saddam built the road in the 90s,” Haidar explained, “at the same time that he drained the marshes. He did it so he could send his tanks in here to kill the people.” I couldn’t understand why anyone would want to kill the Marshland Arabs, but later I read that he was targeting the Sunnis.

After breakfast Abu Raad took us to meet his wife and daughters in a courtyard of his home, behind the hut. They did not speak English so we touched our hearts and repeated “Shakrun,” thanking them for their hospitality. We gave money to Raad to say thank you and he held each of our hands as he said goodbye. He was leaving to go to work at a hospital nearby at the same time we were leaving to go to our next destination.

We drove toward Nasiriya to see the Ziggurat of Ur. There was a fierce windstorm and we could barely see through the sand, which filled our eyes and ears and hair. Haidar didn’t have sunglasses and shielded his eyes with his hand. Ali walked backwards. An old man showed us around the ruins, some as old as 6000 years. The Ziggurat itself, a stepped pyramid built of adobe, mud and reeds, dated back to the 2000s BC. We climbed to the top but the wind-driven sand was brutal on our faces and we didn’t stay long.

We drove toward Nasiriya to see the Ziggurat of Ur. There was a fierce windstorm and we could barely see through the sand, which filled our eyes and ears and hair. Haidar didn’t have sunglasses and shielded his eyes with his hand. Ali walked backwards. An old man showed us around the ruins, some as old as 6000 years. The Ziggurat itself, a stepped pyramid built of adobe, mud and reeds, dated back to the 2000s BC. We climbed to the top but the wind-driven sand was brutal on our faces and we didn’t stay long.

The drive to Babylon from there was several hours and we fell asleep intermittently, waking up to see nothing but dust through the windows. Babylon was a bewildering maze of excavated and unexcavated archeological ruins with reconstructed features of the palace and gardens. An outgoing caretaker who went by the nickname Mekki, clearly a friend of Haidar’s, toured with us and showed us calligraphy and fossils we might otherwise have missed. The only other visitors were a group of Iraqi tourists, all men. We wandered through arch after arch in the reconstructed part of the grounds, stopping to take photos.

The drive to Babylon from there was several hours and we fell asleep intermittently, waking up to see nothing but dust through the windows. Babylon was a bewildering maze of excavated and unexcavated archeological ruins with reconstructed features of the palace and gardens. An outgoing caretaker who went by the nickname Mekki, clearly a friend of Haidar’s, toured with us and showed us calligraphy and fossils we might otherwise have missed. The only other visitors were a group of Iraqi tourists, all men. We wandered through arch after arch in the reconstructed part of the grounds, stopping to take photos.

“This is my throne!” Haidar proclaimed, stopping in front of a raised platform that was apparently Alexander the Great’s. I tried to take a photo and Haidar shook his head. “No, no, no, no, no!” he said, taking the phone out of my hands. “Not like that, like this, see?” He framed the throne platform expertly and flicked the night setting on, as it was getting dark.

Karen was dying to see Saddam’s Babylon palace, which we could see up on a hill beyond the gardens. Haidar had told us it was abandoned and desecrated, vandalized by American soldiers in 2003 after Saddam was taken out of power.

“It is only open during the day,” Mekki said, “but I will take you. My brother is policeman, he give us permission.” We drove up the hill with Mekki in the car with us. It was completely dark when we arrived, and several Iraqi policeman in the courtyard in front of the main entrance gave us containers of water and welcomed us. We used our phones as flashlights and wandered the dark, empty, cavernous rooms. Graffiti covered the walls and the glass was shattered from the windows, but there were still intact chandeliers and elegant murals high up on the walls. In a front room Mekki described as Saddam’s throne room he showed us that if you stomped your foot on one spot on the floor it sounded different, reverberating through the room. This was where visiting dignitaries were to stand and salute Saddam with a stomp of one foot.

“How often did he come to this palace?” Karen asked.

“He come several times while it was being built but he only slept here once,” Haidar said.

Mekki told us when the American soldiers came, many locals took artifacts from the palace and hid them to preserve Iraqi history. He had taken several stone tablets himself but he was arrested and tortured for it. He mimed having his arms tied behind his back and showed us scars on his arms. We didn’t fully understand but Haidar said something about a hole in his diaphragm and that he was in the hospital for eight months.

I wandered through a few rooms on my own and it was unnerving. The shadows on the wall made the graffiti menacing and wind blowing through shattered windows scuttled leaves on the floor. I came to a wall that said “NOT HERE” in English and I turned back, looking for the rest of the group.

There were several staircases, but they were barricaded with barbed wire. “No one allowed up there,” Haider told us. And yet, twenty minutes later I heard we were going to be let upstairs, courtesy of Mekki’s brother, who had given him a key to a back stairway that must have been for servants. We were excited.

“Someday when Iraq is a major tourist destination these kinds of shenanigans will no longer fly,” Ina remarked. I laughed. “And we’ll say, ‘we were there way back when…’”

Upstairs was even spookier than down. We stayed together, walking slowly through the rooms, starting on the fourth floor and working our way down. In the very front of the top floor, a huge room with floor to ceiling windows overlooked Babylon gardens. We thought it must be the bedroom, but we came to more grand rooms that had bathrooms attached so we could not tell which was the master. One had a marble garden tub.

It was late when we left the palace and we went straight to our hotel in Najaf, skipping dinner after our late lunch of kebab. Our hotel was shockingly contemporary and comfortable, on par with an American business class hotel. It had glass elevators ascending the courtyard from the lobby. The room rate was only $70 USD. I took some photos and posted on Facebook for all those friends back home who were so certain I was in peril in a war-torn third-world country.

only $70 USD. I took some photos and posted on Facebook for all those friends back home who were so certain I was in peril in a war-torn third-world country.

I dressed in an abaya and hijab the next day for our shrine and mosque visits in the holy city of Najef, considered by Shi’ites to be the fourth holiest city in the world. Haider had said we needed to buy Iraqi abayas, which looked like squirrel suits, but I was hoping I could get away with my abaya from Yemen because the Iraqi abayas were ugly and not something I wanted to spend money on. Haidar looked me up and down in the lobby and said he wasn’t sure.

“We will ask at the shrine of Imam Ali,” he said.

“But Karen and I have to buy something, right?” Ina asked. Haidar nodded.

It was Friday and the city was crowded. We crawled through stop-and-go traffic on the main street and into a cemetery that Haidar said was the largest in the world, with thirty million graves. We parked and walked through a crowded market where Karen and Ina found abayas. I had to buy socks, since bare feet in sandals were not allowed. Finally, we were ready for the shrine of Imam Ali, first Imam of the Shi’a Muslims, whom we had learned was the cousin of the prophet Mohammed and later became his son-in-law. We went to a separate entrance for women, the “ladies frisking cabin.” Women pressed and pushed against us, jostling each other to get in. I could feel other women’s breasts pushing into my back and I regretted not bringing a mask; we were packed like sardines.

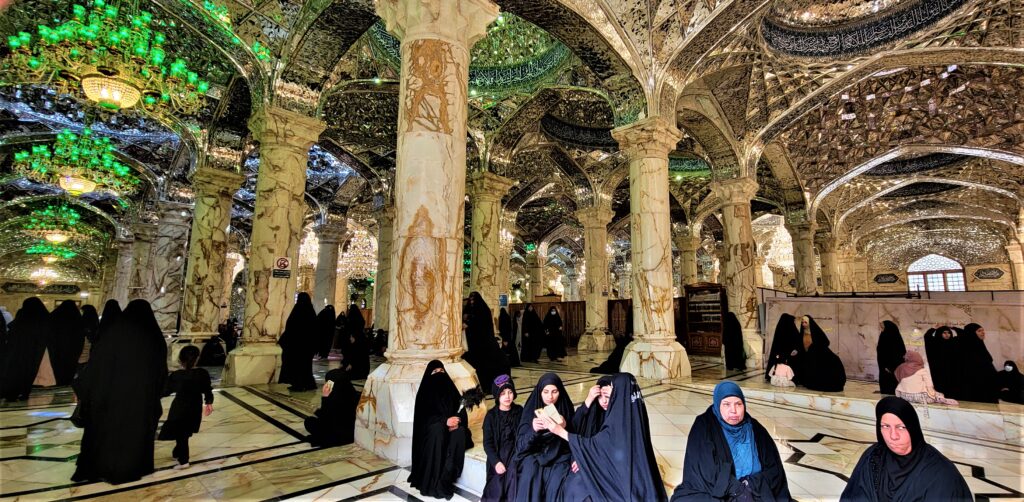

Inside the shrine, the walls and ceilings sparkled with glass tiles and ornate chandeliers. Women hugged and kissed the walls and clutched prayer beads. Signs on the walls said, “no photography” and at first, we obeyed them, but then we saw a few other women surreptitiously snapping photos so we did too. There were women stationed at corners with green feather dusters, security guards of a sort, and when they caught us taking a photo they shook the feather dusters in front of our phones and frowned at us. In some rooms women sat on the floor and socialized, and in others some of them lay on the carpet taking a nap. We walked around in a circuit, entranced by the architecture.

“I’ve never seen so much bling,” Ina said.

There was a mosque after that, and another shrine in the home of Imam Ali. I was mosqued out. We went back to the market for a sweet dessert that tasted like baclava with coconut added, and an even sweeter cup of tea.

Our hotel that night was a high rise with glass elevators again, in the holy city of Karbala. It had been closed for Covid and had just reopened a month ago, and there were very few guests. We had a couple hours to ourselves before dinner so we went to the restaurant on the roof, where we could see the entire city. It was bigger than we’d thought and filled with colored lights. There were only three other guests and they were smoking shisha.

“Maybe we should stay here for dinner,” Ina suggested. I nodded. I was tired and it seemed like they could really use the business.

But Haidar had a different idea when we messaged him. “I am not sure the food is very good there,” he said. “I want to take you on a driving tour of the city and we’ll go to a good restaurant.”

Karbala was Ali’s home, so we went to his house first and met three of his four children. His wife Asmaa came out to say hello and we invited her to join us. The restaurant was glitzy, a long narrow fountain running down the middle. The menu had a good mix of western and Iraqi food and the Iraqis ordered pizza and steak while the westerners ordered Iraqi food. There was a biryani with chicken and some kind of mashed bread topped with a tender beef that fell off the bone.

There were more beautiful mosques and shrines the next day. We learned more about Imam Ali’s family while visiting the shrines of his brothers, Abbas and Husayn. In the shrine of Imam Husayn, where Husayn was martyred, we endured the crush of pushy women kissing walls again and then Haidar told us to wait. He was trying to get something, some kind of permit. We stood for a while, then sat on the carpet. A man with a brown feather duster told us to move. We moved to another wall and sat again. Another man shook his feather duster at us and told us to move. We noticed only the women got hassled about sitting in the wrong places. Haidar said we were getting a photography permit and permission to have lunch and go to the museum. He explained that the shrine was very wealthy, having invested donation money wisely over the years, and it funded many good works including a dining room that fed hundreds of people every day at no charge.

There were more beautiful mosques and shrines the next day. We learned more about Imam Ali’s family while visiting the shrines of his brothers, Abbas and Husayn. In the shrine of Imam Husayn, where Husayn was martyred, we endured the crush of pushy women kissing walls again and then Haidar told us to wait. He was trying to get something, some kind of permit. We stood for a while, then sat on the carpet. A man with a brown feather duster told us to move. We moved to another wall and sat again. Another man shook his feather duster at us and told us to move. We noticed only the women got hassled about sitting in the wrong places. Haidar said we were getting a photography permit and permission to have lunch and go to the museum. He explained that the shrine was very wealthy, having invested donation money wisely over the years, and it funded many good works including a dining room that fed hundreds of people every day at no charge.

An hour passed, and Haidar motioned that it was time to go to lunch. We walked down a hallway and through a tall wooden door with a guard in front. Inside was a small lobby with a male receptionist on a computer. He waved us into a dining room with long tables to seat 50 or 60 people. We were pointed to a different table than Haidar.

“Can’t Haidar come with us?” we protested. The waiter shook his head. “What if we say he is our son?” I asked, to no avail.

“It will be OK, grandma,” Haidar said. He had taken to calling us his three grandmothers, or habibis, which made us laugh.

We sat with 20 or 25 other women and were served plates of rice and chicken. The three women across the table from us were from Lebanon and spoke French, so Ina and Karen were able to talk with them. I tried to follow along. They were talking mostly about their visit to Iraq and what they had seen. They invited us to the lobby afterwards for small cups of thick, rich, sweet Iraqi coffee and Haidar took our photo together. Then he said it was time to go to the museum.

tried to follow along. They were talking mostly about their visit to Iraq and what they had seen. They invited us to the lobby afterwards for small cups of thick, rich, sweet Iraqi coffee and Haidar took our photo together. Then he said it was time to go to the museum.

On the way to the museum, we suddenly found ourselves ushered up a staircase into a suite of rooms signed “Media Department,” through what looked like a gift shop and into a private office. Two women in black abayas and hijabs sat silently on one wall and smiled at us. We sat on couches on the other side of the office and listened patiently to a dark-suited executive, apparently the director of the media department, as he welcomed us formally and began to lecture us on the history and traditions of Islam. He said that women were free in Iraq and could do as they pleased, but they chose to wear the abaya and hijab out of respect for cultural tradition. He spoke in Arabic and paused for Haidar to translate every few minutes. Then he asked if we had any questions.

“I would like to know what the media department does,” I said.

“They have two television channels and some social media pages,” Haidar translated. “They educate the people about Imam Husayn’s history and sacrifice, as well as Shia Muslim traditions.”

“And these women are visitors, or working here?” I gestured across the room.

“They work here,” Haidar said. We asked them to introduce themselves and they did. One of them was in charge of social media, the other worked with the television station.

Karen and I whispered to each other.

“Women are free but they can’t be introduced to us or be part of the conversation,” I said.

“Yes, and we wear the abaya willingly out of respect for tradition but the men don’t have to wear the dishdasha,” Karen said.

“We should ask them about that.”

“I dare you!”

Finally, we were allowed to leave. The men in the gift shop offered us gifts on the way out and Karen and Ina accepted a coffee cup and some refrigerator magnets.

“How did that happen?” I demanded of Haidar when we were out of earshot.

“What do you mean?”

“How did we end up there, in the office of the minister of propaganda? Did he invite us or was it your idea?” I asked, using Karen’s recently coined term for the director.

Haidar laughed. “It was my idea, to get the permit,” he confessed. Haidar had pimped us out, we joked.

We went to the museum and the director showed us around. Someone asked a question and he said, “I would really prefer to sit down with you and explain things to you.” I snuck a panicked look at Haidar and saw him trying not to laugh. We were all tired. It was agreed that we would take a few photos instead and then we would leave. A man with a DSLR camera came out and posed us in a few different places, including a spectacular hallway with identical painted arches in symmetrical succession with the gold domes of the minarets in the background.

We went to the museum and the director showed us around. Someone asked a question and he said, “I would really prefer to sit down with you and explain things to you.” I snuck a panicked look at Haidar and saw him trying not to laugh. We were all tired. It was agreed that we would take a few photos instead and then we would leave. A man with a DSLR camera came out and posed us in a few different places, including a spectacular hallway with identical painted arches in symmetrical succession with the gold domes of the minarets in the background.

It was time to leave for Baghdad. In the car Haidar asked if we wanted to go to a bakery and I said no. We had been eating too much and too many sweets. My saying no had become a joke by now, however, and Haidar had started to call me Grandma No. We went to the bakery anyway and it turned out to be no ordinary bakery. It was a legendary old family business called Bab alagha Bakery, founded in 1948, and immensely popular. There were busses in the crowded parking lot and hordes of shoppers inside. We wandered through aisles and bakery cases of breads, sweets and baked goods. We sampled a few things and Ina and Karen bought boxes of assorted sweets. A man invited us upstairs to the owner’s private quarters and we sat in a living room decorated with photos dating back to the 60s showing members of the family with various visitors, some of them celebrities. The owner, Abu Amjad, welcomed us personally and showed us around. We watched a documentary about the origins of the bakery and then he brought us to his office and began to give us gifts. First coins, then plaques, then baseball caps with the name of the bakery on them. Out on a balcony Haidar pointed to a large building complex across the highway and told us they also owned a yeast factory.

and Ina and Karen bought boxes of assorted sweets. A man invited us upstairs to the owner’s private quarters and we sat in a living room decorated with photos dating back to the 60s showing members of the family with various visitors, some of them celebrities. The owner, Abu Amjad, welcomed us personally and showed us around. We watched a documentary about the origins of the bakery and then he brought us to his office and began to give us gifts. First coins, then plaques, then baseball caps with the name of the bakery on them. Out on a balcony Haidar pointed to a large building complex across the highway and told us they also owned a yeast factory.

“I have 800 employees,” Abu Amjad told us, proudly.

“Is he married?” Ina quipped. We had noticed his Rolex watch.

We went back to Abu Amjad’s office and he showed us an antique wooden icebox. Then he opened a chest in the corner of the room and began to pull out liquor bottles, gifting us a bottle of Dewars.

“Dewars is the best because it is a family business,” he said.

I whispered to Haidar, “We need to go before he gives us anything else.”

We took our loot back to the car. I put on a Bab alagha Bakery baseball cap over my hijab. We were just on the outskirts of Baghdad and now we began to see the high rises and lights of the city. We passed a roundabout with many fountains and colored lights, two contemporary high-rise hotels towering over it, the Palestine and the Ishtar. Karen said the Palestine Hotel had been shelled years ago and was considered the dangerous Western place to stay, like the Intercontinental in Kabul.

We pulled into the Oskar Hotel, which Haidar said was nice and also cheaper than the places we had been staying. I went in with him to check it out and a stylishly dressed woman at the front desk gave us a room key. The room was in a different class from the hotels we’d been staying in so far; it was passable but very worn. The carpet was stained and frayed, the furniture scratched, the windows dirty. But it was $36 per night and the hotel seemed full of interesting international travelers. I went down to the car and told Ina and Karen, “We’ve been spoiled so far and it’s not what we’re used to. But I think it’s OK.”

We checked in and I unpacked a few things since we would be staying two or three nights. There was a knock at the door and it was Karen.

“Ina isn’t comfortable here, she wants to move,” she said. I groaned. I didn’t love it either, but I was tired and didn’t feel like moving, and I had discovered that the wi-fi was fast. I went down the hall to look at Ina’s room and I could see why she was uncomfortable. The door was cracked as if someone had tried to kick it down, and there was hair in her bathroom sink and garbage in her wastebasket. I should have inspected more thoroughly before saying it was clean. We went back to Karen’s room and called Haidar while Ina went online to see what else was close by.

We told Haidar the situation and discussed the pros and cons of splitting up. Karen was on the fence. Finally, we decided Haidar would take Ina to the Baghdad Hotel down the street and Karen and I would stay. I went to bed.

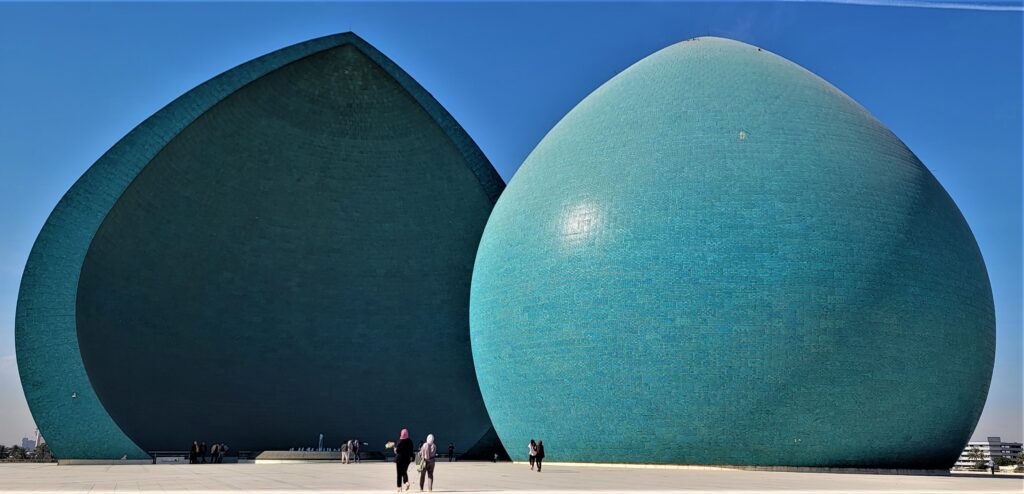

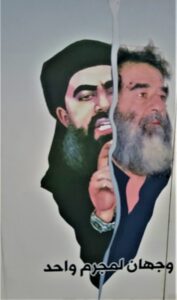

Our first stop on Sunday was the Al-Shaheed, the Martyrs Monument, built by Saddam in 1983 to commemorate the Iran-Iraq war. Two turquoise half domes faced each other with a fountain and a statue of the Iraqi flag in the middle. There was a museum underground, below the monument, and it was closed to the public but Haidar had done something to get us in. We paid an entrance fee and several Iraqi men  accompanied us downstairs by the fountain, which flowed to the level of the museum. We went through a set of glass doors and wandered exhibits in a circular display room. There were paintings, photographs and sculptures memorializing victims of Saddam; some were graphic depictions of torture and murder, others were stately portraits of the people he had killed. Display cases held some of the victim’s belongings. One especially impactful display showed photos of the aftermath of ISIS attacks juxtaposed with Saddam’s trail of destruction, and a painting of Saddam and al-Bagdadi, the leader of ISIS, suggested they were one and the same. At the end of the display was a painting of Saddam’s head with a noose around his neck, the caption reading “End of a tyrant.”

accompanied us downstairs by the fountain, which flowed to the level of the museum. We went through a set of glass doors and wandered exhibits in a circular display room. There were paintings, photographs and sculptures memorializing victims of Saddam; some were graphic depictions of torture and murder, others were stately portraits of the people he had killed. Display cases held some of the victim’s belongings. One especially impactful display showed photos of the aftermath of ISIS attacks juxtaposed with Saddam’s trail of destruction, and a painting of Saddam and al-Bagdadi, the leader of ISIS, suggested they were one and the same. At the end of the display was a painting of Saddam’s head with a noose around his neck, the caption reading “End of a tyrant.”

“He would roll over in his grave if he knew the memorial he built to the Iran-Iraq war was now a memorial to all the people he killed,” Karen remarked.

We went to the Taq Kasra, also known as the Arch of Ctesiphon, an ancient Persian ruin from somewhere between the 3rd and 6th century AD. For some reason the police at a checkpoint just before we reached the ruins insisted we needed security and some of them jumped into a jeep and escorted us. I asked why, and Haidar said it was because of the recent ISIS attack nearby in al-Rashad. We came to a dead-end street and got out of the car in front of a fence with police guarding the gate. Haidar talked through the fence for several minutes and finally said, “We cannot get a permit to go inside. They say it is too dangerous because of rebuilding work. But we will drive around to the front to take photos.”

We drove away. Suddenly all the police were gone, and we joked that it must have been my blonde hair and not security concerns that interested them. But I looked up the al-Rashad attack on Wikipedia and it had happened only a few weeks ago. ISIS operatives had killed 11 people in the village. Iraq declared victory over ISIS in 2017 after taking Mosul from the terrorist group, but random sleeper cells remained in rural areas.

From the front, the arch was impressive. Haidar pointed to a paved path that led from the arch to another building perhaps a quarter mile away. He said Saddam had built it in that precise location to send a message to Iran, “We are watching you.” We parked in a cul de sac and took a dirt path through a garbage dump.

“Hurry,” Haidar said. “I don’t want anyone to see us, it is not allowed.”

We went into the abandoned building, which Haidar called a panorama. It smelled like it had been burned. We waded through rubble and up the circular staircase in the middle of the building. On the first level we came out into a dark space in which we could see the hanging, ruined frame of something that had once moved in a circle around the center stem of the building. There was etching on the walls that we couldn’t see clearly. We went further up the stairs, to the roof. We could see policemen in a golf cart coming down the path from the Ctesiphon and Haidar told us they were looking for us and we should hide. We crouched behind a pillar until they left.

I couldn’t understand what I was meant to see in the panorama until I read about it later. “In the early 1980s, Hussein ordered the construction of a panorama in the shape of a terraced Mesopotamian ziggurat to commemorate a 7th-century battle in which Arabs defeated a Persian army. Dozens of North Korean artists painted battle scenes on a 16,000-square-foot screen that was the third largest in the world.” The article was written in 1999, when the building was still open and functioning, but it said that visitors could no longer hear the clatter of armor and shouting of warriors because the sound system no longer functioned due to lack of spare parts and electricity.

Karen had posted in a Facebook group called the Iraqi Traveler’s Café that we wanted to meet some locals, and that we would be at the bar in the Baghdad Hotel that evening. The hotel was luxurious compared to the Oskar. A bomb-sniffing dog circled the car while security guards checked our credentials at the gate. Inside, we crossed a lobby and went up an escalator to the outdoor pool on the second level. It was lit a cool blue and had a bar next to it. Servers wearing miniskirts and black patterned stockings strolled leisurely between comfortable seating areas with sofas. We met Omar and AJ, who had come together, and Kum. They were young, in their late 20s and early 30s, and all lived in Baghdad but had traveled extensively. Their English was the best we’d heard since arriving. We ordered alcohol, the first time we’d seen it available, and talked about traveling. Kum was a dentist who had lived in Ukraine for ten years after doing his medical degree there. Omar was an IT consultant who traveled frequently throughout the Middle East and Eastern Europe for work, and AJ was in the import business. They talked to us about the corruption of the Iraqi government and what it was like to live here as educated, well-traveled Iraqis.

time we’d seen it available, and talked about traveling. Kum was a dentist who had lived in Ukraine for ten years after doing his medical degree there. Omar was an IT consultant who traveled frequently throughout the Middle East and Eastern Europe for work, and AJ was in the import business. They talked to us about the corruption of the Iraqi government and what it was like to live here as educated, well-traveled Iraqis.

Monday was to be our last day in Baghdad and we had a long list. We drove to the market in the old city and saw many old things – the oldest juice shop, another long-time family-owned business that sold delicious raisin juice; the oldest clock tower in Baghdad; and the oldest Islamic school, now closed, but dating back 850 years. We had tea in an old, family-owned tea shop known as a hangout for poets and intellectuals. Karen and Ina shopped for copper tea pots and silver jewelry, and I bought some small Iraqi carpets. We had lunch in a dumpling shop, famed for its Iraqi meat dumplings. Then we asked Haidar if we still had time to see Abu Ghraib and Fallujah. We didn’t know if there was really anything to see there, but Karen and I both had a fascination with conflict-related destinations.

Haidar said we could go but it would be almost dark when we got there. Traffic was terrible and it took a long time to get out of the city. At one point we sat in gridlock, cars all pointing inward toward a middle point from which no one could get out, all honking their horns pointlessly.

Abu Ghraib looked just like any prison; stark stone and cement buildings surrounded by barbed wire and guard towers and a giant stone wall on the perimeter. But there were spotlights shining from the guard towers and at least one of them had an armed soldier in it.

“I thought Abu Ghraib was closed?” I said.

Karen shook her head. “I don’t think so,” she said. “I think I read that it was being used by the Iraqi government now.”

I looked up the Wikipedia entry I’d been reading before and showed it to her. It said Abu Ghraib was closed in 2014. She shrugged. No one knew.

We could tell we were coming close to Fallujah when the checkpoints began. We’d been through many checkpoints since the start of the trip, but this was different. There were three or four of them and they were staffed very heavily with hordes of military police, many of them wearing full combat gear and helmets with headlamps and GoPros on them. They were still very friendly but they were more serious  than the other police we had met. They took our passports at every checkpoint and asked many questions. At the last one a crowd of them came to my window to talk to us. There was one man wearing a blue suit and he spoke some English. He smiled at us and introduced himself importantly as the director of police intelligence or something like that.

than the other police we had met. They took our passports at every checkpoint and asked many questions. At the last one a crowd of them came to my window to talk to us. There was one man wearing a blue suit and he spoke some English. He smiled at us and introduced himself importantly as the director of police intelligence or something like that.

“You are very welcome here,” he said.

“Thank you,” I said. “We are very pleased to be here. We have heard there is much rebuilding going on.”

“Destroyed,” one of the other men said.

“But now rebuilding, right?” He nodded, proudly.

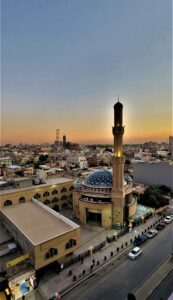

We drove into the city and it was indeed a mixture of crumbling buildings with bullet holes and shiny new storefronts. There was a minaret with the top blown off and Haider said ISIS had done that. There were military police on every corner and lining the streets, and in some spots there were tanks. We’d never seen such heavy security. We turned when we got to the Euphrates and drove along the riverbank, which was lined with restaurants. We came to the famous Fallujah bridge, where the Blackwater contractors had been hung in 2004 after being burned and dragged through the streets. It was undamaged and unremarkable. It was obvious that this was a city returning to some semblance of normality but not without great effort.

Haidar said it was time to go and we headed back to Baghdad, stopping to take photos in front of the “I Love Fallujah” sign. We stopped for falafel and to see the square where Saddam’s statue had famously been tumbled after his arrest in 2003. It was now a beautiful public space surrounded by fountains and lit with multicolored lights.

Haidar said it was time to go and we headed back to Baghdad, stopping to take photos in front of the “I Love Fallujah” sign. We stopped for falafel and to see the square where Saddam’s statue had famously been tumbled after his arrest in 2003. It was now a beautiful public space surrounded by fountains and lit with multicolored lights.

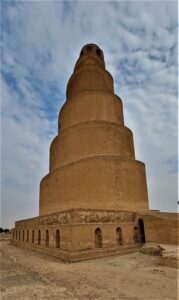

We left earlier than usual the next morning. It was a long drive to Mosul, and we had stops planned along the way. Three Portuguese tourists we had met when we first checked into the Oskar were caravanning with us, following in their own car with a driver and another guide who worked for Haidar. Our first stop was the famous spiral minaret in Samarra, a slightly tilted tower with a staircase winding around the outside and leading to the top. I gripped the handrail all the way up, feeling a slight vertigo. At the top Iraqi boys clowned around and pushed each other and there were no rails. I sat on a step just below the top, afraid to go any further, but Ina and Karen sat at the very top while Ali, the other guide, took their photo. The Iraqi boys took turns having their photos taken with me until one pushed the other very close to the edge and I’d had enough. I headed down.

There was a mosque in Samarra that Ina and Karen wanted to visit but I was done with mosques. I said I would stay in the car. Haidar said Ali had to go with the other driver to fix a tire on the Portuguese tourist’s car so I would have to go with him.

We got into Ali’s SUV and drove to a garage. The owner welcomed us as if we were visiting a café. I was shown to a chair made of old tires like a throne and a young boy brought me an orange drink. The owner showed me photos on his phone of various creative things made of old tires, brightly painted different colors – planters, chairs, tables, decorative items. He said he sold them.

I watched two young boys, probably the sons of the owners, fixing the tire. I could see from the corner of my eye two men standing by an old beat-up car glaring at me. It was the first time I’d felt nervous. After several minutes of trying to pretend I didn’t see them I remembered the doctor in the Basra airport who had said to be friendly to the men. I turned my gaze directly on them, put my hand on my heart, smiled broadly and said, “Salem.” The men smiled back. One of them came to talk to me and rolled up his pants leg to show me his deformed lower leg. Most of his calf muscle was missing and the top of his tibia bone bulged.

“Daesh,” he said, the Iraqi word for ISIS.

Back in the car I asked Haidar to translate the story from Ali. ISIS had put a car bomb in the man’s car, and he was very badly hurt. Ali said the government had refused to compensate him.

We went to lunch, all sitting together at one big table. The three Portuguese men had traveled together many times; any time their wives didn’t want to go, they joked. One of them, Victor, was working on visiting every country in the world and only had about 30 left to go. We compared notes on some of the more difficult countries. Mario said their guide in Pakistan, where they had been just prior to Iraq, said he could take them to Afghanistan.

“Now?” I said, incredulous.

Mario shrugged. “He said it’s fine, the Taliban won’t bother you.”

I wondered if that would be true for women travelers, or just for men.

We ate a huge lunch; salad, bread, soup, tikka chicken. Iraq food so far seemed to consist of food from other Middle Eastern or central Asian countries like falafel, kabab and shwarma. Nothing seemed to be identifiable as uniquely Iraqi, other than the meat dumplings in Baghdad, although everything had been delicious.

We headed north again and the landscape became desolate; dry, dusty desert with occasional fortress-like structures manned by military police, or ruined mosques. Every structure was full of bullet holes. We went through a checkpoint where Haidar knew people and he jumped out of the car to hug a few of the police. There was a crowd of uniformed men on the side of the road and Haidar explained that they were volunteer fighters who fought ISIS for years until the government finally recognized them and began to pay them.

“Volunteer fighters?” Karen asked. “Doesn’t that make them militia?” No one really knew the answer to that question. The men got into their jeeps and trucks and drove by us in a procession and Haidar said they had been here for a memorial service.

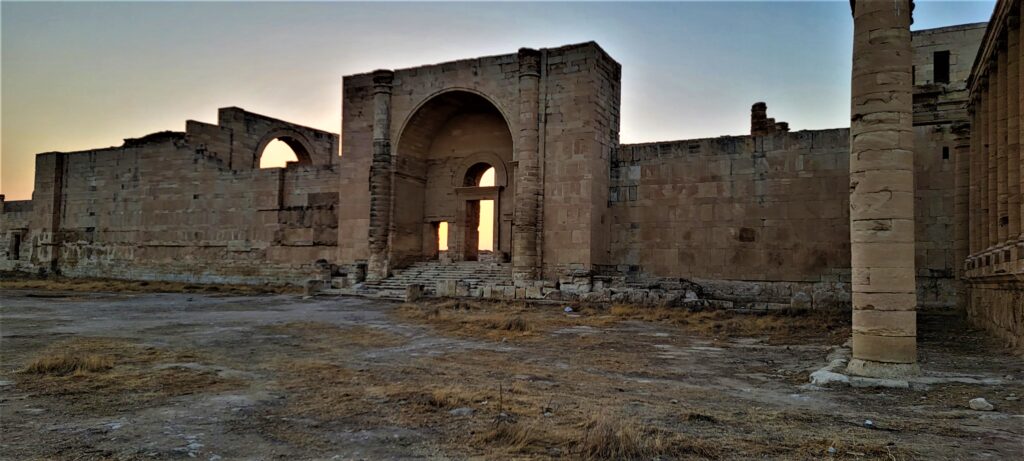

We were going to Hatra next, and this was a special treat; Haidar had phoned ahead to get us a permit. Hatra is the site of Arabic ruins dating back to the third century BC, and it was one of several sites Saddam had partially restored because he saw them as reflecting glory on himself. The ruins had been occupied by ISIS from 2014 to 2017, along with the rest of the province, who used it as a training ground for new recruits and set up shooting ranges throughout the site. When Hatra was finally liberated from ISIS in 2017, it was feared that the ruins had been destroyed, but it turned out very little damage had been done despite the terrorist’s efforts. Now, an Italian restoration company was painstakingly putting the site back together. Several military police and security guards came with us and Haidar said we could walk through the ruins but we couldn’t take photos inside, by order of the Italian restoration company. Five or six military policeman and security guards walked with us through the site as sunset arrived, creating a glow behind the ancient ruins. Haidar showed us Saddam’s name stamped into the bricks of the restored portions.

We arrived in Mosul an hour later and were surprised at the size and vibrance of the city. There were high rises and brightly lit buildings and we drove down a street lined with restaurant after restaurant, all busy, and an amusement park. We turned in at a sign that said “tourist complex” near the Tigris River and Haidar explained that most of the hotels had been destroyed during the ISIS occupation and there were few options for lodging now. We had several small one-bedroom apartments in separate bungalows, one for the Portuguese guys, one for the two guides and two drivers, and after some negotiation, two bungalows for us so that we didn’t have to have one person sleeping on a mattress in the living room.

We decided the next day we would just have one day in Mosul and then head up to Iraqi Kurdistan. Our tour with Haidar and Ali was supposed to be finished the next day, but we had asked if we could book them for some additional days in Kurdistan. They would be staying with us three more days, until Sunday, when Haidar had to return to Baghdad for another client.

I talked to Mario, one of the Portuguese, outside our bungalow while waiting for Ali and Haidar to pick us up.

“It’s really a shit country, isn’t it?” he said.

I was taken aback. “What do you mean?”

“It’s all just trashy cities. There are no traditional villages.”

I hadn’t really considered that. “We saw a traditional village in the marshes,” I protested.

“We didn’t, we just saw these plastic huts.”

“We saw traditional huts where they live from farming water buffalo,” I told him. “And I think it’s an amazing country. Their hospitality in the wake of many conflicts, a brutal dictatorship, famine, foreign interference…it’s unfathomable.”

Mario shrugged. We had heard that the Portuguese travelers had been difficult to deal with. They hadn’t experienced the same friendliness of the locals and especially the police that we had, and we’d speculated it was because they simply weren’t projecting the same openness and friendliness that we were. I silently thanked the Ukranian doctor from the Basra airport who had given advice about being friendly to men. He thought he was just talking about our safety, but it was more than that.

We went to breakfast at an outdoor restaurant that served a very thin crust pizza-like dish with fried egg on it. Then we went to the old city, photographing bombed-out buildings along the way. We drove through a fish market to the entrance to the worst part of the old city, which had been designated as a UNESCO world heritage site. Military policemen stopped us and explained there was a film crew doing a documentary today and we would need to be quick. In passable English, one of them said, “Only take photos and do not go inside any building or touch anything. There is a bomb.” We laughed, understanding that he meant there might be unexploded ordinances inside the buildings.

We wandered a narrow alley through the burnt-out, crumbling ruins of the old city, taking photos. I had read that during the final battle with ISIS, in 2017, their primary weapon was a SVBIED, a vehicle filled with explosives and a suicide driver welded inside that would wreak total destruction on everything around it. The consensus of people I asked seemed to be that this part of the city would not be rebuilt.

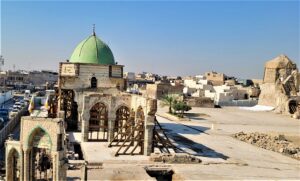

We went to a mosque Haidar said was the place ISIS leader al Bagdadi first declared victory over Mosul. It was now partially destroyed; I read later that when ISIS began to lose Mosul, the last thing they did was destroy some of the more prominent mosques, a signal of defeat. We went upstairs in an abandoned building to get a better view.

We went to a mosque Haidar said was the place ISIS leader al Bagdadi first declared victory over Mosul. It was now partially destroyed; I read later that when ISIS began to lose Mosul, the last thing they did was destroy some of the more prominent mosques, a signal of defeat. We went upstairs in an abandoned building to get a better view.

The Portuguese tourists needed to leave for Baghdad now, and the apparently complicated process of getting gas for both cars began after that. For reasons I never understood, Kurdistan had, in Haidar’s words, “taken all the gas from southern Iraq.” We thought he must be exaggerating at first. We went to a place that was heavily guarded and a local policeman got in the car with us. We drove to a gas station that had a long line of cars all the way down the street, waiting for a pump. The policeman waved us to the front of the line and we gassed up in just a few minutes.

“So, if we were not foreigners would we be able to get gas?” I asked Haidar. He shook his head. “The locals know not to even come,” he said.

We took the policeman back to where we’d picked him up and thanked him. Haidar said we had time to see one more thing so we would go to the ruins of Nimrud, just north of the city. These were ancient Assyrian ruins that had also been restored by Saddam but then occupied by ISIS, and they had not fared nearly as well as Hatra. We drove up an embankment to a gate where two security guards got into the car and escorted us to the site. Once again, Haidar had gotten us into something that was not open to the public. The guards and several military policemen walked around with us to show us what little was left of the site. The entrance archway was still standing but after that it was rubble. We walked through the ruins with a man who had been a caretaker here since 2004. He said ISIS blew it up with 28 barrels of TNT and it was like seeing his family blown up for him. He showed us the original well, and the remains of the palace prison, and a hammam (bathtub) that was still intact and had been part of the king’s daughter’s chambers.

We came to the Kurdistan border about an hour after Nimrud and parked there. Haidar told us to wait, and he and Ali got out and walked toward the immigration office. When Haidar came back he said, “We may have a problem. They don’t like Ali’s documentation and they don’t want to give him a visa.”

We were shocked. Apparently, it was of so little of concern for us to cross the Kurdistan border that they hadn’t bothered to have us check in yet, but Ali was being denied.

“Why?” I asked. Haidar shrugged. “They can do what they want. They just don’t like him.”

“Can we help?” I persisted. If white privilege had any use in this world I was not above employing it for this. “Can I tell him he is my driver and I need him or else I can’t go?”

Haidar shook his head. “No,” he said. “I am calling my friend Baderkahn in Kurdistan to see if he can help, and Ali is still trying to talk to them.” Baderkahn was a well-known travel blogger and tour guide that Haidar had worked with before.

“What’s plan B if it doesn’t work?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” Haidar said. He considered for a moment, looking very troubled. He left again, and while he was gone we bought bags of potato chips from a snack stand in the parking lot. We hadn’t eaten since breakfast.

Haidar came back. “They will not let him in,” he said. “I am so, so sorry.” Haidar looked very sorry indeed, as well as humiliated. “Baderkahn is in Mosul and he can be here in half an hour to pick you up, but I cannot go with you because I will have to help Ali to drive back to Baghdad. But I can come back up here tomorrow.”

We protested. If Haidar had to go all the way back to Baghdad it made no sense for him to come back up to Kurdistan. But it felt like a terrible way to part, and we were all upset.

“Let’s go have your passports checked,” Haidar said. We got out of the car and walked toward the immigration office. Suddenly, Ali appeared, walking toward us and smiling broadly.

“We go!” he shouted, ‘go’ being one of his few English words.

“You got it?” we shouted back, incredulous. We didn’t understand how he had managed to change their minds, but it didn’t matter. The problem was solved.

We went into the immigration office where there was a long line for the locals and a short line for foreigners. Three men stood at the line for foreigners and Ali cut in front of them to hand in our passports. It felt like another white privilege moment and we whispered uncomfortably to each other, but we didn’t completely understand the situation; it might have been that we just had a simpler task for the clerk, because he glanced briefly at our passports and handed them back. We went back to the car and drove through the checkpoint, stopping again for a passport check and to have our bags examined. Then we were in Kurdistan.

As I had heard, it was like another country. As we drove into Erbil the main road was lined with clean, modern, brightly lit gas stations, mostly devoid of customers. The city was large and sprawling, dotted with high rises. If you ignored the storefronts with Arabic writing on them it felt like a western city.

We checked into the Erbil View Hotel, renowned in traveler circles as a decent hotel for a good bargain. Haidar wanted to take us out to a market area across town for dinner but we were tired and said we’d have something light in the hotel’s seventh floor restaurant and call it an early night.

It was Thursday, and Ina’s last day; she was flying home for a wedding over the weekend. We spent the day in Erbil, walking first to the citadel, a World Heritage site dating back to the 5th century BC, which had been undergoing a restoration project since 2007. There was a textile museum to visit and an antiques shop, but otherwise it was deserted. We visited the bazar, a large, bustling marketplace radiating out from a circular building of stalls selling everything from food to clothing to appliances. In the evening we watched the sunset from the top floor of our hotel, then went to the busy street food area Haidar had talked about the previous night, called Iskan. We ate roasted turkey, tomatoes and onions wrapped in thick pieces of bread, standing on a street corner and watching people go by.

“This place is full of life,” Haidar said. “But it is mostly men here and I think if you walk around they will stare at you and say things.”

“We don’t care,” Karen said, and Ina and I agreed. We wanted to see the street vendors cooking things. Haidar shrugged. “Ok, but wear your scarves,” he said. We walked down one side of the street and up the other. There were stands with Turkish sweets, kebab, roast chickens, piles of rice with vegetables in them, soups and stews. A few vendors had bubbling vats of what looked like intestines cooking in gravy.

“It’s Ina’s last night,” I said. “We should go to a bar and have a glass of wine and maybe some desert.” Ina had often asked for a glass of wine during the trip but except for at the Hotel Baghdad, it had never been available in the places we ate and stayed. “Can we go to a restaurant or maybe a nice hotel that has a bar?”

“The front desk clerk at our hotel said the Hotel Divan is the nicest hotel in Erbil,” Karen said. I wanted to check it out.

The Hotel Divan was 21 stories high and had a spa, five restaurants and a piano bar. The doorman told us to go to the 21st floor, where we found a sushi restaurant that served alcohol. Ina and I drank wine while Ali, Haidar and Karen had orange juice and sweets. We stayed out until nearly 10:00 pm.

At breakfast the next morning we met two British travelers who said they were traveling with Joan Torres of Broken Compass, a well-known travel blogger amongst off-the-beaten-track travelers. We introduced ourselves to him the lobby and met his group of seven or eight people, mostly Europeans and one American. They were using Erbil as a base and today, they were going to a mountain town where they had rented a house through their local guide, Karwan, whom we knew by reputation. We told the group we hoped to see them again when we all returned on Sunday. This was the second time we had met a travel blogger leading a group, after running into Janet Newenham in the old city in Mosul; it had started to seem like the entire adventure travel world had chosen this time to visit Iraq.

The car felt a little empty without Ina. We checked out of the Eribil View Hotel and headed north, into high desert mountains very similar to western Colorado and Utah. In the town of Lalish we went to the temple of the Yazidi, a holy village where Yazidis make regular pilgrimages.

Yazidism is an ancient monotheistic religion dating back 7000 years, and its practitioners have long been persecuted, most recently by an ISIS genocide attempt. The man credited with founding the religion, Sheikh Adi Ibn Musafir, is buried in a tomb at the temple of Lalish. Haidar said we must leave our shoes in the car because the place was so holy that people went barefoot even outside. We walked up the narrow road through the village and a uniformed Kurdish man escorted us to a building with one large room, couches lining every wall. Other visitors sat drinking tea, and a man dressed in traditional Kurdish costume ordered us tea and sat with us. His English was very good and he had a sense of humor, although I didn’t understand all of his jokes. Next to us sat a young French couple who were on holiday from university in Cairo and had been touring around Kurdistan for a week. They said they were hitchhiking and staying in locals’ homes.

“We’re too old to do that,” Karen said. I nodded. “We would have done it when we were your age though,” I said.

Our host stood and motioned to us. “Come, it is time to have the lunch,” he said.

We walked under an arch and up stone steps to a terrace, then into an alcove with cushions on the floor. There were other alcoves off the terrace where we could see families sitting on the floor, eating from communal bowls of food. We sat with the French couple and shared bowls of rice and lamb, bread, fresh cucumbers and tomatoes. The French couple told us about their travels. They had gone up to the Iranian border and said it was very cold there.

It was time to visit the shrine after lunch. We went into a building, stepping over the stoop as instructed, and down a staircase into a cave. Jars of oil lined the walls, and we could hear an underground spring gurgling beneath us. We came to one room where a large family was taking turns throwing a scarf on top of a pillar. Yazadis believe your wishes will come true if you can get the scarf to stay on the pillar for three tosses.

We ducked through a low archway into another cave where a man dressed in a caftan and turban sat guarding the tomb of Musafir. He lit pieces of incense, swirling them in front of us. He pointed to a small stack of Iraqi dinars on the stone in front of him, indicating we needed to make an offering. I took a 250 bill out of my purse and put it down, and he flicked it onto the floor of the cave and frowned at me and shouted “La, la!” He waved his hand as if to tell me to get out of the cave.

Haidar looked mortified. “I think we better get out of here,” he said, and we turned to leave. Behind us we heard the man laughing and I realized he was just teasing me. “La, la!” I shouted at him, crossing my arms. “I don’t want to come in now!”

We ducked through one more low archway into the last cave where the tomb was. We each walked up two stairs to the shrine, closed our eyes, then walked backwards down the steps. The shrine was considered so holy you were not to turn your back on it.

We left the shrine and drove to the mountain town of Al Qosh, a Chaldean Catholic village which had an ancient Catholic monastery carved into the mountainside called Rabban Hormizd. A checkpoint guarded the town; soldiers asked us to leave our passports and told us to visit only the monastery and then come  right back. A road switchbacked up the mountain, followed by stone steps switchbacking to the terraces and caves of the monastery. We were met by a man who introduced himself as the priest and gave us a tour of the main chapel and a series of dark caves leading from it. We used our phone flashlights to wander the caves, sometimes stooping through narrow passageways with low ceilings. The priest said different parts of the monastery had been founded at different times, but 640 AD was generally the year ascribed to its origin. The caves offered lodging for the monks as well as an escape hatch. ISIS had not penetrated this place, miraculously.

right back. A road switchbacked up the mountain, followed by stone steps switchbacking to the terraces and caves of the monastery. We were met by a man who introduced himself as the priest and gave us a tour of the main chapel and a series of dark caves leading from it. We used our phone flashlights to wander the caves, sometimes stooping through narrow passageways with low ceilings. The priest said different parts of the monastery had been founded at different times, but 640 AD was generally the year ascribed to its origin. The caves offered lodging for the monks as well as an escape hatch. ISIS had not penetrated this place, miraculously.

That night we stayed in the city of Dohuk, another surprisingly large and modern city, this one flanked by mountain ranges on either side. We checked into a basic hotel called the Krystal and went out for dinner in a kebab restaurant with a nice atmosphere.

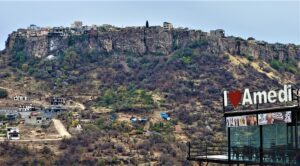

“Tomorrow we have lots of driving,” Haidar told us over dinner. “We will go to see Amedi and then we drive many hours to Sulaymanyia.” Amedi was an ancient Assyrian town perched picturesquely on a plateau and Karen had been eagerly awaiting the photo opportunities. Suly, as Haidar called it, was the other major city in Iraqi Kurdistan besides Erbil.

We set off the next morning after a luxurious breakfast in a fancy restaurant with chandeliers and a piano player. Haidar treated us to breakfast and told us to eat well because we wouldn’t have time for lunch. It was chilly and raining, but we stopped many times outside of Amedi trying to get the perfect photo, one that captured the fact that Amedi was perched on a raised plateau.

was chilly and raining, but we stopped many times outside of Amedi trying to get the perfect photo, one that captured the fact that Amedi was perched on a raised plateau.

“This is the city where the three kings came from,” Haidar explained on the drive. “They walk from here to give the gifts to baby Jesus.”

We drove up into the town and through narrow streets, parking at a very old mosque where Ali went to pray. Karen and I walked through a market, smiling and saying hello to the townspeople. We noticed only men were on the streets and in the cafes and shops.

“Where are all the women?” Karen asked when Haidar came out of the mosque. He shrugged. “They are at home cooking the dinner, maybe, I don’t know.”

We looked at each other. “Scrubbing the kitchen floor, no doubt,” I said.

The drive to Suly was long, as promised, but beautiful, staying mostly in the mountains. We went through the town of Barzan, where the family who governed Kurdistan lived, and we saw several large and elegant homes Haidar said belonged to the family. There was a cave in which Neanderthal remains had been found only a few years ago, but it was closed.

We arrived in Suly just in time for dinner. Haidar had an economical hotel in mind but said we could also stay in a nice hotel if we wanted to pay $100. We chose the nice hotel. Haidar pointed in the distance to a high-rise building glowing bright purplish blue with a flying saucer on top. “The Millennium,” he said. The flying saucer was a revolving restaurant.

stay in a nice hotel if we wanted to pay $100. We chose the nice hotel. Haidar pointed in the distance to a high-rise building glowing bright purplish blue with a flying saucer on top. “The Millennium,” he said. The flying saucer was a revolving restaurant.

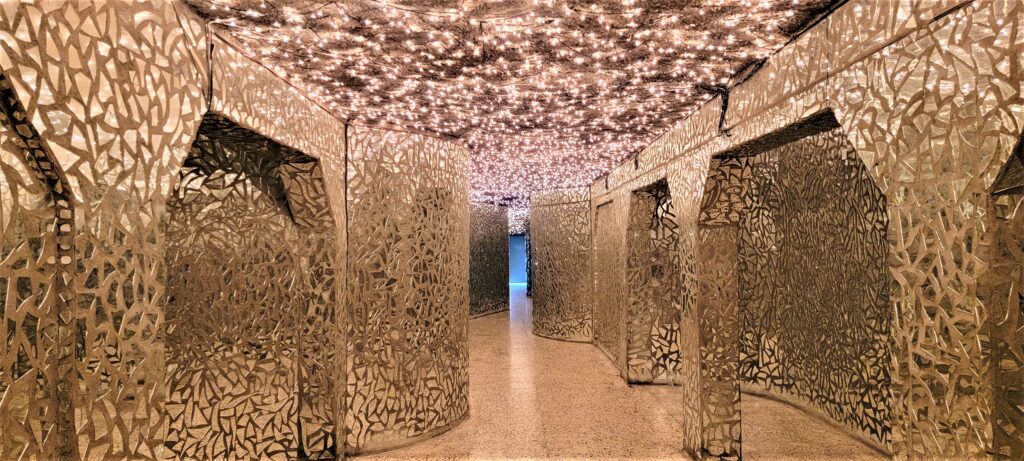

The next day was our last with Haidar and Ali, and we had a full itinerary planned. It was a sobering, even depressing, day. We went first to the museum at Amna Suraka, the Red Prison, which housed Iraq’s intelligence agency during Saddam’s reign. Many people were imprisoned and tortured there, especially students and Kurdish nationalists. Boys as young as 15 were locked up and their ages changed to 18 so they could be executed. There was a beautiful hall of mirrors, with a shard of glass to memorialize each victim and a light in the ceiling for each village. After that, the exhibits were tough to see: tiny, windowless prison cells with hopeful and hopeless messages written on the walls; re-creations of torture and interrogation chambers; photos of the thousands of peshmergas who gave their lives, including an entire squad of women; photos of ISIS militants with raised swords about to descend on a neck or a wrist or an ankle. We wandered the museum in silence.

From there we drove north to the museum in the village of Halabja, where the largest chemical attack by Iraqi forces on the Kurds took place in 1988, after Iran-backed Kurdish peshmerga guerillas captured the village. Iraqi planes dropped mustard gas and nerve agents, killing an estimated 5000 and injuring another 7000, mostly civilians. A museum caretaker who survived the attack as a 15-year-old boy showed us around the museum. It was full of heartbreaking photos of dead Kurds, including many children, some with dark fluid oozing from their mouths. The caretaker told us he was blind for six months and spent several years in Iran recovering before returning home. His entire family was killed.

Our last stop for the day was a picturesque mountain village on the Iran-Iraq border. We crossed a river and hiked a short distance on a trail that intersected an aqueduct; one side was Iraq and the other Iran. There was a sign hanging from a tree that showed a bearded elderly man serving tea and Haidar said we would go see if he was there today. We followed the aqueduct until it came to a circle of sofas sitting amongst the trees with a rustic little outdoor kitchen, but the man was not there today, so there was no tea.

We went back to Sulaymaniyah, where Haidar and Ali had planned to put us in a taxi to Erbil so they could take the more direct route to Baghdad, but we had the idea to go back to the Millennial Hotel and have one more luxurious night. We said goodbye to Haidar and Ali in the lobby and went to the revolving restaurant at the top for a drink while we waited for rooms to be ready. The view of the city was worth the price of my martini. Just before we were ready to leave a group of travelers arrived and it turned out to be Joan Torres’s group again; they had just finished a day of touring Sulaymaniyah and had stopped for a drink. They told us they would be back at the Erbil View the next day too.

We knew we’d feel the lack of ease and convenience once Haidar and Ali were gone, but we didn’t know just how much. Our taxi came for us at 9:00, and a young American man named Neboysa, Boysha for short, asked if he could join us. He was Serbian but had lived most of his life in California and was traveling for an indefinite amount of time after quitting his second tech start-up. We were enjoying our conversation with him when we came to the provincial border between Erbil and Suly and the driver motioned that we needed to get out with our passports. Haidar had always handled checkpoints for us before and we’d never had to get out of the car.

The military police at the checkpoint did not speak any English. He pointed at the stamps in our passports and seemed to be asking where we were coming from, or maybe where we were going.

“Basra, Baghdad, Mosul, Erbil, Sulaymaniyah, Erbil,” Karen said, miming the journey with one hand.

“Baghdad?” the policeman questioned. He handed Neboysa’s passport back to him, seeming not to have any problem with it, but he held on to ours. He spoke into his phone in Kurdish and the phone said something like, “Not to have a permit to Kurdistan.” We looked at each other in confusion. The man motioned to us to go outside to talk to his boss. We went out of the office and into a courtyard, talking with another policeman over the top of a concrete wall. He too looked through our passports in detail and then motioned for us to walk around the wall and into another office.

A man who was apparently in charge sat in the second office. He took our passports and we went through the routine again.

“Basra, Baghdad, Mosul, Erbil, Sulaymaniya, Erbil.”

He spoke into his phone and the phone said, “Hotel booking Erbil.” He spoke again and the phone said, “Flight.”

It had begun to dawn on me that we had a problem. I dialed the Erbil View hotel and asked the woman who answered if she could speak to the police and confirm our reservation. When I held the phone out to the man in charge he said, “Kurdish?” I nodded. He took the phone but handed it back quickly.

Karen meanwhile had produced her flight reservation. I didn’t have one, having not yet decided exactly when I was leaving, but it didn’t seem to matter, since Karen’s wasn’t making an impression.

“Go back to Sulaymaniyah,” the man in charge said, dismissively.

I dialed Haidar and explained the situation. I asked the policeman if he spoke Arabic and he shook his head in disdain. “Kurdish,” he said firmly.

“Just wait,” Haidar said, “I will call Bahderkahn. He will fix this.”

The policeman shooed us out of the office, clearly done with us. We waited in the courtyard, uncertainly, apologizing to Boysha for getting him into this mess. He shrugged.

“No worries,” he said.

Haidar called back and said Baderkahn was on the taxi driver’s phone and would speak with the police. We could see our driver, a quiet, gentle Kurdish man, following the policemen meekly as they ignored him to deal with some other problem at the border patrol booth. Finally, he got them to take the phone, but they didn’t keep it for very long.

Haidar called me again and said, “They are stupid, they don’t know the rules. You will have to take a different route.” Boysha was OK because he had flown only to Kurdistan and had a Kurdistan visa, but we had crossed a land border from federal Iraq and had only our Iraqi visa. It was legal for Kurdistan, but a combination of ignorance and bias seemed to be at play.

The taxi driver took Boysha across the border on foot and showed him to a taxi on the Erbil side. We drove to another border crossing, holding our breath. Haidar had said if this crossing didn’t work there was one more we could try, far away, and then we would have to give up and go back to Suly.

At the second crossing the border police seemed friendlier. We still had to get out and show our passports but they let us through after minimal inspection. We pulled up to the Erbil View Hotel as if we were arriving home after a long and stressful journey, and Boysha was in the lobby, having just arrived himself.

I decided to stay at the Erbil View Hotel for the remaining six days of my trip. Joan’s group was back at the hotel and beginning to trickle out, one by one, but that gave us several travelers to do things with, plus Boysha. Karen and Boysha and I went to a Syrian refugee camp north of Erbil, a visit Karen had been planning since she read Joan’s blog. We took a taxi to the camp, a sprawling settlement of tin-roof shacks and administrative buildings. We were paraded from office to office at first, starting with a security office where no one spoke English and we drank tea and looked at each other and burst out laughing for no reason. Then we went to the office of Mr. Botan, whom Karen had originally set the meeting with, and he told us about the camp. It was sponsored by UNHCR, the United Nation’s Refugee Agency, and the Barzan Charity Foundation, which we recognized as the family name of the power establishment in Kurdistan. The camp had been in existence for seven years and for reasons we couldn’t quite understand, the schools were now closed because there was some sort of seven-year limit on UN funding for them. There were about 2400 families living here, with about 11,000 individuals, and it was like a village complete with shops and restaurants owned and run by the residents themselves. Mr. Botan said they all had residency and could leave whenever they wanted.

“Why is there a fence around the camp if they can leave?” Karen asked.

“It is more to keep out than to keep in,” Mr. Botan explained. “We keep out animals, and people who don’t belong, and also it is how we know how many people live here.”

Another man, some sort of aid to Mr. Botan, took us into his office for more tea while we waited for the woman who managed the cultural center, herself a Syrian refugee. It had been suggested that she would be the best person to distribute the coloring books and school supplies we had brought with us. When we met with her we used an app on her phone to translate that we wanted her to make the gifts rather than doing it ourselves. We had heard from others it was very uncomfortable to be swarmed by children when you didn’t have enough to give something to each of them.

“We trust you to make the decisions,” Boysha spoke into the phone. She nodded.