Ghibabo’s Italian restaurant was just down the street from the Crystal Hotel and reviews described it as one of the best in Asmara. It was mostly open-air, a series of terraces surrounding a courtyard lit with a canopy of little white lights in the trees. A man in a black suit with the air of a manager greeted me at the door. “Are you Italian?” he asked. “I am!” I said, without thinking. “By descent, that is. I was born in the U.S.” He seemed delighted by this and said I should have a tour of the restaurant. He took me into the one fully enclosed room full of glass cases with Italian artifacts and very old bottles of wine mounted on the walls. “We call this the museum room,” he said proudly. We went to a second room with shelves displaying decorative silver serving pieces across one wall. It was early for Eritrean dinner, only 6:30, but there were full tables here and there with what looked like friends socializing over coffee or beer.

A third room, more of a terrace above the courtyard, had festive colored light bulbs strung along the walls and a man played an electronic keyboard, his knees bouncing with the music. He smiled as I came in and I took a photo. “I’ll sit here!” I told the manager. He sat me at a table for two facing the musician and brought me a menu.

I ordered a fish curry and it was served by the chef himself, a jovial man who came out of the kitchen to say hello. “What do you think of Trump?” he asked. The 2024 U.S. elections had just wrapped up as I was transiting through Istanbul and I had been hoping Eritrea would be a distraction from the election results.

“I am very upset,” I told him honestly. “He’s not good for our country. But what do the Eritreans think?”

“We think he will be good for everyone,” the chef said, to my surprise. “He does not like war. He will bring peace to the world.”

I considered whether this might be true. I didn’t think I should say what was on my mind, which was that Trump likely didn’t know Eritrea existed and would call it “one of those shithole countries” if he did.

The servers began moving furniture to set up a long dining table next to me. The manager came to oversee them as they scurried about with chairs and silverware and it seemed like an important group of people must be coming. I hoped they wouldn’t be a noisy family with lots of children. I counted 14 chairs and it dawned on me to ask, “Do you know who made the reservation? Are they locals or tourists?”

“I think they are locals,” he said. “A local man named Jacob made the reservation and they should be here at 7:30.”

Jacob was the name of my tour group’s Eritrean guide, and there should be about 14 people in the group, I mused. I had missed the first two days of the tour during an unplanned detour in Istanbul and I was now waiting for them to come back from an overnight trip to Senafe, in the southern mountains of Eritrea. I decided there was a good chance it was them, so I ordered another glass of sweet local wine and waited.

I saw the manager speaking with a tall, Spanish-looking man with a beard when the group came in, gesturing toward me. The man turned and recognized me right away.

“Anna? I am Oriol,” he said, pumping my hand. Oriol was our Spanish tour leader from Against the Compass. “Everyone is at the hotel looking for you!” I realized I had miscalculated. Of course they would be looking for me; I should have gone back to the hotel after dinner.

The group filed in, introducing themselves. They were a friendly bunch, and like most ATC groups they were from all over the developed world – Finland, Sweden, Spain, Austria, the UK, Australia, the US, Canada. The last to come in were my friends Ina and Karen, who had stayed longest at the hotel looking for me. “We even had the front desk unlock your room, just in case…” Karen trailed off.

In case I had checked in and died? I wondered.

The next day, I began to learn more about the history and culture of Eritrea. This was usually a learn-as-you-go endeavor for me — but I usually had the ability to read up on what I hadn’t retained from our guide on the internet later. Eritrea was a different story. We had been told to expect no internet at all, no outside news media, no social media. Some of what I knew was from Karen, whose husband was an international human rights attorney and had led a successful lawsuit against a Canadian mining company operating in Eritrea several years ago. The lawsuit accused the company’s Eritrean management of beating employees, tying them out in the sun for hours, paying them just $30 dollars a month and punishing them if they needed to take any sick time.

Eritrea had only one political party, the unelected People’s Front for Democracy and Justice, and it was synonymous with a government that had ruled with an iron fist since the country first gained independence from Ethiopia in 1993. Abuses by the Eritrean military, including torture, gang rape, imprisonment and execution without trial, and other human rights abuses had led to U.S. government sanctions in 2021.

Our guide was very frank about the brutal repressiveness of his government, which did not tolerate dissent. Jacob had an interesting family story. He was the only one of his immediate family left in Eritrea. His father had immigrated to Scandinavia as a refugee of the Ethiopian war 15 years ago, followed by his mother immigrating to the U.S. His brothers and sisters were spread out around the globe. As we left our hotel on a bus, he explained to us that Eritreans had a duty to indefinite civic and military service from the age of 18. Until the age of 55, they did not have passports and could only leave the country illegally, and if they wanted to come back they had to sign a document admitting guilt and send the government 2% of their earnings for at least two years. Then they would be sent a passport and allowed to return.

“Why did you choose to stay?” I asked him.

“I have a good life here. I have a government job and my own tour company. If I left and started over, it would be hard for me.” Jacob was in his early 40s.

We made a few stops around town – the main market, a fruit and grain market, a coffee shop, and a place called the recycling center. Jacob explained that during the time of the Italian occupation, beginning in the 1920s, the Italian government didn’t allow Eritreans to go to school past fifth grade. They created the recycling center as a sort of trade school, where children could learn to make things, and it remained a place of instruction and manufacture to this day. We walked through and saw women learning to grind and sift grain, and men learning to weld metal or make rubber. It was a busy, noisy place.

In the market, we heard loud car horns. It was a wedding procession, cars painted in white, a photo of the bride and groom taped to the windows of each car. Everyone on the bustling streets stopped to watch and cheer. We went to a coffee shop and found some of the wedding party there, the men all dressed in immaculate white suits, some with top hats. The Italian influence, left over from the occupation, was still very visible in Asmara — but it was the Italy of yesterday, a 1940s Italy. What I couldn’t reconcile was how approachable and friendly people were. They smiled and welcomed us everywhere we went and it didn’t feel like a repressive culture.

At 3000 meters, Asmara had offered a cool and comfortable temperature but we’d been warned that we would be descending to the tropical lowlands, where temperatures could be in the 40s Celsius. We drove roads with hairpin turns down from the mountains into lush green valleys, full of cactuses. Karen told me the Italians planted the cactuses to keep the earth from eroding as they planted on hillside terraces, and the cactuses proliferated and persisted, despite not being native to the land.

The heat made me drowsy and I slept on and off. At one point I heard someone shout, “Look, baboons!” The bus stopped and we all rushed to one side. I couldn’t recall if I had ever seen baboons that close before. Their faces and rear ends were strikingly ugly: gashes of red calloused skin and mean, beady little eyes too close together. Jacob had known we would see the baboons and he had bushels of bananas. He threw them out the window, one by one, and baboons stormed the bus in groups of three, five, ten. They glared at us as they ate their bananas. A mother ran by with a baby baboon on her back and even the baby was ugly.

“Good thing we’re in here, they can be vicious,” someone said.

We stopped in a small village for lunch, in a dusty restaurant with a courtyard. Jacob must have called ahead because they were waiting for us. They set up a long table in the main room with a little buffet table full of unidentifiable dishes and I tried a bit of everything.

“What was the dish with the little orange chewy bits?” I asked Jacob after. “Those were sheep and goat intestines,” he said. I was glad I’d waited until afterwards to ask. They were good.

We sat in the courtyard and a woman served us a hot, incredibly strong cardamon and ginger coffee. I poured sugar into it and still could barely drink it. A man offered a bottle of ouzo to the group but I didn’t dare drink in the heat. Auli, an outgoing older woman from Finland, said, “Pour me two!” She drank nearly half a glass. On the porch of the restaurant, as we loaded the bus, she set her eyeglasses askew and pretended to stumble drunkenly for our amusement.

After several more hours of switchbacks we reached the lowland floor and we could feel the heat like a heavy, wet blanket. Massawa was a coastal town, spread between the mainland and two islands connected by causeways. Our hotel was on the first island, right next to the causeway to the second island, where the old town was. We stopped there to walk around.

“This is where I grew up,” Jacob explained. “It was once a very busy, very prosperous seaport. My father worked for the shipping companies and there were big ships at port all the time, taking exports to the places the British were colonizing. Now, we call it the ghost town.”

It was indeed. We passed a huge, crumbling bank building and circled through the alleys of two-story whitewashed stone buildings that looked long abandoned. There were several storefronts with restaurant signs but they were empty. Scattered children played in the dirt, and every few blocks we’d see someone lounging on a day hammock, escaping what must have been terrible heat inside the buildings. It was hard to imagine anyone lived here. Jacob told us his family still owned a house, but he didn’t point it out. We wondered if it was because it was too raw for him.

We went inside a very old mosque. Outside, Auli played with the children, pretending to charge at them, and one of them hid behind a pole and ran from her laughing. “These children, they only know about playing. They don’t know that they’re poor,” she remarked when they were out of earshot.

It was almost evening, and I was terribly hot. My feet were filthy from walking the alleys in sandals. Jacob said we would check into the hotel and come back to the old town for dinner, but that if anyone was too tired they could eat at the hotel.

“I don’t really recommend it though,” he warned. “Stick to eating either pasta or fish.”

Candace, a well-traveled American woman I’d been chatting with all day, was clearly as hot and tired as me. She asked if the hotel restaurant was air conditioned. Jacob shook his head. “It is outside on the ocean though,” he said. “You’ll have a breeze.”

The Dahlak Hotel was right across from an abandoned palace that had once belonged to Haile Selassie, the emperor of Ethiopia between the 1930s and 1970s. The lobby was cavernous, with several stone-tiled sweeping stairways curving up to the guest room floors. I was relieved beyond words to see an air conditioning unit in my room, but then I couldn’t get it to work. The heat and humidity were unbearable. I took a shower, hoping for cold water but settling for a room temperature trickle. I lay on the bed under a ceiling fan and immediately began to sweat again. I went downstairs to ask for help and thankfully, they moved me to another room where the aircon worked. After a second shower, I was cooled enough to have dinner in the hotel restaurant with the ocean breeze.

We left the hotel early the next morning, walking across the causeway for breakfast in the old town. The bus came to take us to the beach, and we stopped along the way to see three tanks on display that had been captured from the Ethiopian Army by the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front. Captions said they were destroyed in the 1990s after crossing the causeway, and one of them said, “after crushing into an enemy armed truck.” Some of the guys climbed up onto the tanks to look inside, a thing that would have been prohibited in the U.S. or in Europe.

After an hour at the beach, Jacob took us to visit a Rasheeda family, a nomadic tribe that was known for racing camels. They lived in tents in the desert, moving between Eritrea, Ethiopia and Sudan. Before we got off the bus he explained a few etiquette rules.

“They can be funny about photos,” he said, “especially the women. We will wait and let them tell us when it is time to take photos. And it would be rude for us to visit and then just leave, so we will need to stay for tea.”

We walked across the desert, sidestepping pellets of camel poop, and came to a tent made of blankets draped over a wooden stick frame. It should have been hot inside but somehow, it wasn’t. A tiny baby goat, with a shriveled umbilical cord still attached to his belly, was tied by one thin leg to the tent frame and the women in the group swarmed around him, taking photos and proclaiming his cuteness. The tent was big enough for all 14 of us to sit in a circle with the members of the family. The woman of the family served a thick, sweet coffee with just a hint of ginger, nothing like the strong brew from yesterday’s lunch. The man of the family offered to dress some of us in the Rasheeda’s traditional dress, long black embroidered robes with matching head coverings that looked very hot. Jacob chose Emil and JayJay to model them because they were the youngest, and we laughed and took photos. Jacob told us more about the Rasheeda.

“They live from farming and from breeding camels for racing. There is a baby camel out there, just born yesterday; we will visit him before we go. Another thing about the Rasheeda, the men can have up to seven wives.”

Someone made the expected joke about leaving JayJay behind as an eighth wife, now that she was dressed as a Rasheeda.

With our coffee finished, the family lined up for photos. There were four men of varying ages and only one woman, so I wondered if this was a family that did not have multiple wives or if perhaps the other wives were hiding from photos. We thanked the family and went out to see the baby camel. He was lying in the dirt, looking helpless, his long neck struggling to support his head and sometimes falling back to the ground. As we gathered around him, his mother hovered nervously over him, nuzzling his neck with her mouth. Jacob explained that it took three or four days for a newborn camel to gain enough strength to stand up. If the mother were on her own, she could feed him only if she lay next to him. But one of the Rasheeda men milked her and hand-fed the baby as we watched. He used what looked like a tea kettle to pour the camel milk into the baby’s mouth.

The bus ride back to Asmara was long but we were going up into the cool air this time. We stopped in Asmara for coffee and Ina was delighted when she saw the Roma Cafe out the bus window, one of the famous Art Deco sights of Asmara. She clapped her hands and began to speak Italian. It was decked out like an old Italian movie theater with black and white square floor tiles, framed photos of early film stars on the wall, and a huge 1920s moving pictures camera on display in the middle of the room. Jacob directed us behind a curtain at the back of the serving area and there was a real movie theater, with an Italian football game running on the screen. This was every bit the Asmara I had read about. But we were not staying this time, we were only transiting through on our way to Keren, along another winding road through the mountains and down to a lower altitude.

We checked into a hotel on the outskirts of town on a quiet road. My room had a balcony overlooking the main road, and the next morning I heard cows and goats on the road, their herders leading them toward a dirt path up into the hills for grazing.

Jacob had said we would have a very busy day exploring Karen. We went to the animal market first, dropping Ina at the jewelry market on the way because she knew she would be too upset to see the way the animals were treated. She was a retired veterinarian.

The animal market was a series of huge dirt courtyards, one for camels and donkeys, another for cows, goats and sheep. Men displayed the animals to each other, sometimes beating them with sticks to get them to move, and the boys were even worse, laughing as they beat them for no apparent reason. I had the idea that the boys were sometimes mistaking their abuse as entertainment for watching tourists, so I moved on quickly. Groups of donkeys were huddled together with their faces to the wall, and it seemed like they were trying to hide from the world, or at least from the sticks. I saw Oriol and asked him about it. He seemed very bothered by the market too.

“I think they are depressed,” he said. “They are trying to escape from the world.”

Later I saw Jacob and asked him the same question.

“Donkeys are near-sighted,” he said, “and can only see about six feet in front of them. They are trained to stand facing the wall so they don’t get distracted and try to run around while they’re being shown to buyers.”

I thought about how we so often project our human emotions on animals. Jacob seemed completely oblivious to our distress about how the animals were treated, having grown up in a community where animals were relied on for so many kinds of work.

We picked Ina back up, who had decided she’d been abandoned because we were late, and went to a tented market in a dry riverbed where clothing and household goods were sold. It was hot and some of us sheltered under a bridge, where a tea vendor had little stools.

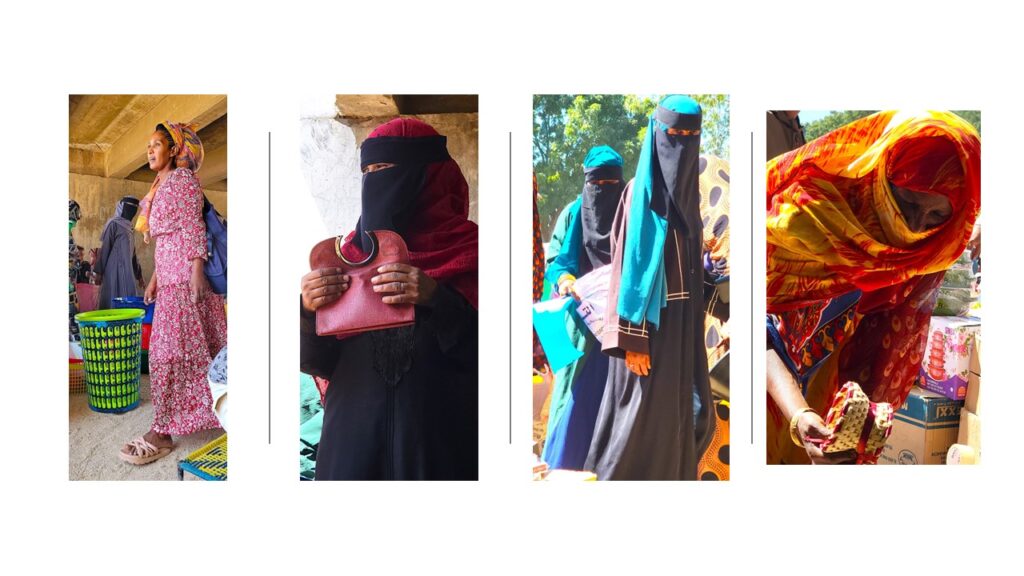

“I’m getting a lot of good photos,” Candace told me. “We’re under the radar here, so the women usually don’t see the camera.” Women in Eritrea were very camera-shy, sometimes downright camera-hostile. I followed Candace’s lead, surreptitiously snapping photos of women as they bargained at the tables nearest to us, one selling washing tubs and another selling kitchenware. Unlike in Asmara, where many women dressed stylishly in Western wear, here most women were in long flowing gowns, many with matching headscarves and a few with veils. Every outfit was completely different; the brilliant colors and patterns were mesmerizing as women fluttered by. One woman caught Candace aiming her phone but instead of yelling at us or walking away, she smiled and posed.

We visited a school for deaf children, where we congregated in the headmaster’s office and one of our Spanish travelers presented him with pens, pencils and soccer balls. The headmaster made a speech to welcome us and took us to a few classrooms, where we said hello and learned some Eritrean sign language. Auli was in rare form, sitting at the desks with the children, looking through their books, shaking their hands, joking with them. Someone asked the headmaster if we could hear what the children wanted to do when they grew up. The headmaster explained that their vocations would be chosen for them; teachers would assess their skills and put them in training programs for specific jobs. Later, he showed us the vocational center where they trained for sewing or welding.

We had a few more stops before returning to Asmara, including an old train station turned bus station, a hotel with an amazing 360-degree view from the roof, and a Catholic shrine inside an enormous baobab tree, said to have been visited by Mary. There was a cemetery where British soldiers were buried, each with a headstone naming and memorializing them, and then a sad cemetery for Eritreans and Italians where every headstone said, “Ignoto” – unknown. The British soldiers wore dog tags and the Ethiopians, Eritreans and Italians did not.

We had a three-hour bus ride back to Asmara again, and Jacob called us to attention before we arrived.

“The tour is almost over,” he said. “Tonight, we will have dinner at Ghibabo restaurant again because it is close to the hotel and we can walk. Tomorrow, we have a few more sights to see in Asmara and then one more dinner together before people begin to leave.” It seemed impossible that the tour was ending already, but of course I had missed two days of it.

At breakfast on our final morning, people were having the country-counting conversation that inevitably happens with groups doing off-the-beaten-track tours. I learned that the two older Spanish-speaking men, Hugo and Jose, had visited 190 and 130 countries respectively. Abbery was at 98 and just starting to get off the tourist track in her pursuit of all 193 United Nations-recognized countries. Karen had somehow jumped up to 94 since the last time I’d asked her. I was a baby traveler in this group, with only about 45 countries, but I had done more of the difficult ones than most people with a low country count. There was no one in the group who wasn’t well traveled, and we all agreed on one thing – Eritrea was a strange place.

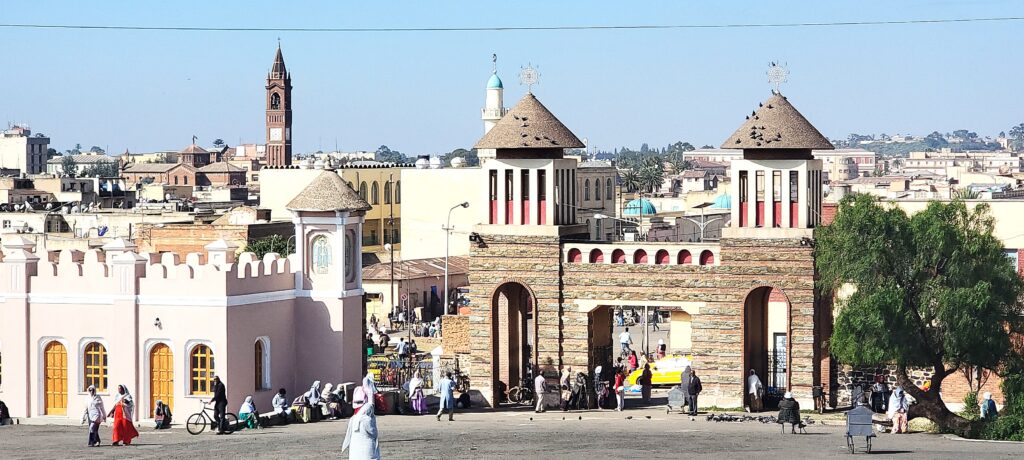

We visited a Coptic church, and Jacob showed us a famous view from the courtyard that encompassed the steeple of a Catholic church, the façade of the Coptic church, and the minaret of a mosque, all close enough to capture in one photo. We went to a hotel known for being the oldest hotel of the Italian occupation era and it was stunning – marble floors, crystal chandeliers, frescos, high archways, hand carved wooden furniture. Some of the guest rooms were open and we toured through them. There were lavish suites decorated in the style of 1920s Italy, full of antiques and paintings. We asked Jacob and Oriol why we hadn’t stayed there, or at least eaten in the restaurant, and they said that sadly, the service was terrible. The owner was the same man who owned the Dahlak Hotel in Massawa, and his focus was there because that’s where the revenue was. He had let his Asmara hotel, as beautiful as it was, become infested with bed bugs and known for surly, slow service.

We walked around the same part of the city I’d explored on my own the day I arrived, and I thought about how much one misses without a local guide. We went into an antique post office, an old Alfa Romeo dealership, and a coffee shop where they played a strange version of billiards, with little pins in the center of the table to be knocked down like bowling pins. We ran into a colleague of Jacob’s, a woman who was showing a Brazilian man around, and they stopped to joke with Oriol and Jacob about how Jacob was allowed to take us to Massawa on his own now. I looked at them quizzically and Jacob explained.

“Asmaran men are not allowed to go Massawa without a special permit unless they are accompanied by a woman,” he said, “because it is so close to the Ethiopian border and many have escaped. The last time Oriol was here, I had to have my colleague come with us to Massawa, but this time I got the special permit.”

We went to a bowling alley that had pool tables and a café and 1980s-style video games. The lanes of the bowling alley looked antique, but to our surprise, a man set up the pins at Jacob’s request and sent bowling balls rolling down the gutters. We amused ourselves for an hour, most of us playing very badly, but Auli and Oscar each had a strike. We cheered and clapped.

After lunch at an Italian restaurant, our last visit was to the private museum of a lifelong collector, available only by appointment, hidden behind a family-owned glass factory. We toured four rooms cluttered with floor to ceiling displays of everything imaginable, spanning decades – radios, cameras, phonographs, knickknacks and curios, statues, coins, stamps, movie posters, furniture, kitchen appliances, old film reels, vinyl records, newspapers, maps, and things that could not be categorized. The owner showed us around with pride. There were several antique cars in the middle of one room, including an Alfa Romeo, and a sign on one of the cars read, “If we lose the past, we lose the future.” The owner told us he had been collecting for 44 years and his family would carry on the legacy. He believed it was critical to instill an understanding of history in young people.

We weren’t allowed to take photos and later I asked Jacob why. He shrugged. “I am not sure, but he is waiting for the government to give him space so he can make this an official museum.”

“Maybe he worries about robbery if people see photos of what’s in here?” I asked, repeating Candace’s theory.

“No, we have a very low crime here in Asmara,” Jacob said.

Our final dinner was at Ghibabo again, which had come to seem like home and the waiters and keyboardist all smiled and welcomed us like regulars. Candace and I mused about the low crime rate.

“Have you ever seen anywhere with so much poverty yet such low crime?” Candace asked. I thought for a moment. “Bhutan, perhaps? But the Bhutanese don’t think of themselves as poor, it’s just our perspective.” We had both been to Bhutan and agreed that there was no crime there at all. Both Bhutan and Eritrea were governed by a single entity, isolated from the outside world, and offered no democratic freedoms to their people. But Bhutan was considered a benevolent monarchy and measured their productivity in “gross national happiness,” whereas Eritrea was a totalitarian dictatorship known for human rights abuses. Perhaps it was simply that Eritreans did not commit crimes out of fear.

Jacob brought three of his children to dinner and they were delightful. The eleven-year-old daughter circulated our group and kissed everyone on the cheek, Italian-style. We imagined they had a much more worldly upbringing than your average Eritrean, given what their father did for a living. I wondered if someday they would escape to another part of the world, after their military service, as most of Jacob’s family had done.

If we lose the past, we lose the future…but if a country hangs on too tightly to the past, what then? Does it become a country whose citizens dream only of escape? Was the European colonial feel of Asmara that intrigued tourists merely a chain and shackle to Eritreans, another sign of their isolation from the rest of the world? Or does an isolated population, lacking exposure to mass media, have the luxury of not missing freedoms they never really knew existed? Perhaps even a totalitarian dictatorship felt like freedom after years of occupation by the Italians, followed by Ethiopian rule, followed by war. I had only questions with no answers, and Eritrea would remain, for me, an enigma.

Comments are closed.